Chapter 2

Kripa said, “We have heard all that thou hast said, O puissant one!Listen, however, to a few words of mine, O mighty armed one! All men aresubjected to and governed by these two forces, Destiny and Exertion.There is nothing higher than these two. Our acts do not become successfulin consequence of destiny alone, nor of exertion alone, O best of men!Success springs from the union of the two. All purposes, high and low,are dependent on a union of those two. In the whole world, it is throughthese two that men are seen to act as also to abstain. What result isproduced by the clouds pouring upon a mountain? What results are notproduced by them pouring upon a cultivated field? Exertion, where destinyis not auspicious, and absence of exertion where destiny is auspicious,both these are fruitless! What I have said before (about the union of thetwo) is the truth. If the rains properly moisten a well-tilled soil, theseed produces great results. Human success is of this nature.

Sometimes, Destiny, having settled a course of events, acts of itself(without waiting for exertion). For all that, the wise, aided by skillhave recourse to exertion. All the purposes of human acts, O bull amongmen, are accomplished by the aid of those two together. Influenced bythese two, men are seen to strive or abstain. Recourse may be had toexertion. But exertion succeeds through destiny. It is in consequencealso of destiny that one who sets himself to work, depending on exertion,attains to success. The exertion, however, of even a competent man, evenwhen well directed, is without the concurrence of destiny, seen in theworld to be unproductive of fruit. Those, therefore, among men, that areidle and without intelligence, disapprove of exertion. This however, isnot the opinion of the wise.

Generally, an act performed is not seen to be unproductive of fruit inthe world. The absent of action, again, is seen to be productive of gravemisery. A person obtaining something of itself without having made anyefforts, as also one not obtaining anything even after exertion, is notto be seen. One who is busy in action is capable of supporting life. He,on the other hand, that is idle, never obtains happiness. In this worldof men it is generally seen that they that are addicted to action arealways inspired by the desire of earning good. If one devoted to actionsucceeds in gaining his object or fails to obtain the fruit of his acts,he does not become censurable in any respect. If anyone in the world isseen to luxuriously enjoy the fruits of action without doing any action,he is generally seen to incur ridicule and become an object of hatred. Hewho, disregarding this rule about action, liveth otherwise, is said to doan injury to himself. This is the opinion of those that are endued withintelligence.

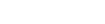

Efforts become unproductive of fruits in consequence of these tworeasons: destiny without exertion and exertion without destiny. Withoutexertion, no act in this world becomes successful. Devoted to action andendued with skill, that person, however, who, having bowed down to thegods, seeks, the accomplishment of his objects, is never lost. The sameis the case with one who, desirous of success, properly waits upon theaged, asks of them what is for his good, and obeys their beneficialcounsels. Men approved by the old should always be solicited for counselwhile one has recourse to exertion. These men are the infallible root ofmeans, and success is dependent on means. He who applies his effortsafter listening to the words of the old, soon reaps abundant fruits fromthose efforts. That man who, without reverence and respect for others(capable of giving him good counsel), seeks the accomplishment of hispurposes, moved by passion, anger, fear, and avarice, soon loses hisprosperity.

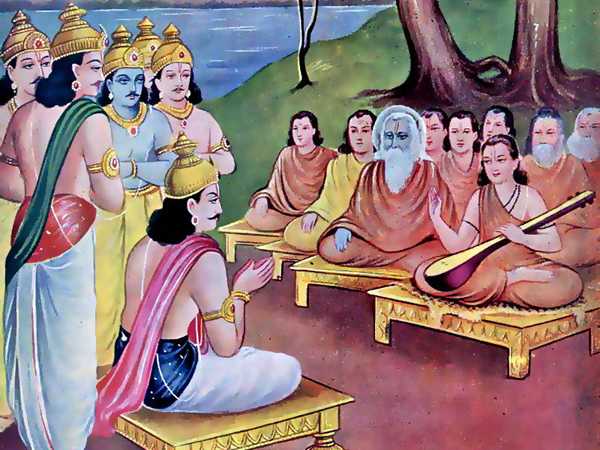

This Duryodhana, stained by covetousness and bereft of foresight, hadwithout taking counsel, foolishly commenced to seek the accomplishment ofan undigested project. Disregarding all his well-wishers and takingcounsel with only the wicked, he had, though dissuaded, waged hostilitieswith the Pandavas who are his superiors in all good qualities. He had,from the beginning, been very wicked. He could not restrain himself. Hedid not do the bidding of friends. For all that, he is now burning ingrief and amid calamity. As regards ourselves since we have followed thatsinful wretch, this great calamity hath, therefore, overtaken us! Thisgreat calamity has scorched my understanding. Plunged in reflection, Ifail to see what is for our good!

A man that is stupefied himself should ask counsel of his friends. Insuch friends he hath his understanding, his humility, and his prosperity.One’s actions should have their root in them. That should be done whichintelligent friends, having settled by their understanding, shouldcounsel. Let us, therefore, repair to Dhritarashtra and Gandhari and thehigh-souled Vidura and ask them as what we should do. Asked by us, theywill say what, after all this, is for our good. We should do what theysay. Even this is my certain resolution. Those men whose acts do notsucceed even after the application of exertion, should, without doubt, beregarded as afflicted by destiny.”