Chapter 87

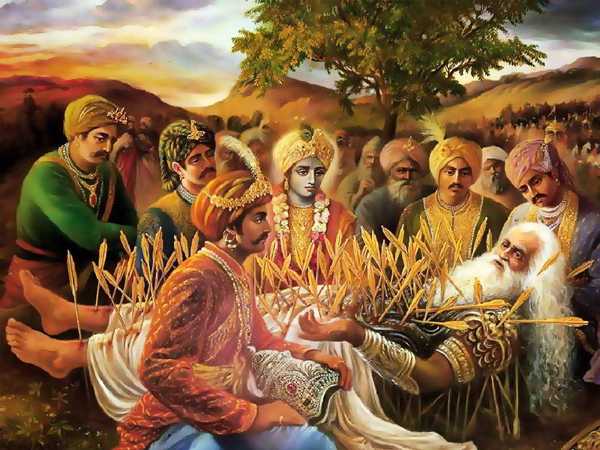

“Yudhishthira said, ‘How, O king, may a kingdom be consolidated, and howshould it be protected? I desire to know this. Tell me all this, O bullof Bharata’s race!’

“Bhishma said, ‘Listen to me with concentrated attention. I shall tellthee how a kingdom may be consolidated, and how also it may be protected.A headman should be selected for each village. Over ten villages (or tenheadmen) there should be cone superintendent. Over two suchsuperintendents there should be one officer (having the control,therefore, of twenty villages). Above the latter should be appointedpersons under each of whom should be a century of villages; and above thelast kind of officers, should be appointed men each of whom should have athousand villages under his control. The headman should ascertain thecharacteristics of every person in the village and all the faults alsothat need correction. He should report everything to the officer (who isabove him and is) in charge of ten villages. The latter, again, shouldreport the same to the officer (who is above him and is) in charge oftwenty villages. The latter, in his turn, should report the conduct ofall the persons within his dominion to the officer (who is above him andis) in charge of a hundred villages. The village headman should havecontrol over all the produce and the possessions of the village. Everyheadman should contribute his share for maintaining the lord of tenvillages, and the latter should do the same for supporting the lord oftwenty villages. The lord of a hundred villages should receive everyhonour from the king and should have for his support a large village, Ochief of the Bharatas, populous and teeming with wealth. Such a village,so assigned to a lord of hundred villages, should be, however, within thecontrol of the lord of a thousand villages. That high officer, again,viz., the lord of a thousand villages, should have a minor town for hissupport. He should enjoy the grain and gold and other possessionsderivable from it. He should perform all the duties of its wars and otherinternal affairs pertaining to it. Some virtuous minister, withwrathfulness should exercise supervision over the administration affairsand mutual relations of those officers. In every town, again, thereshould be an officer for attending to every matter relating to hisjurisdiction. Like some planet of dreadful form moving above all theasterisms below, the officer (with plenary powers) mentioned last shouldmove and act above all the officers subordinate to him. Such an officershould ascertain the conduct of those under him through his spies. Suchhigh officers should protect the people from all persons of murderousdisposition, all men of wicked deeds, all who rob other people of theirwealth, and all who are full of deceit, and all of whom are regarded tobe possessed by the devil. Taking note of the sales and the purchases,the state of the roads, the food and dress, and the stocks and profits ofthose that are engaged in trade, the king should levy taxes on them.Ascertaining on all occasions the extent of the manufactures, thereceipts and expenses of those that are engaged in them, and the state ofthe arts, the king should levy taxes upon the artisans in respect of thearts they follow. The king, O Yudhishthira, may take high taxes, but heshould never levy such taxes as would emasculate his people. No taxshould be levied without ascertaining the outturn and the amount oflabour that has been necessary to produce it. Nobody would work or seekfor outturns without sufficient cause.[251] The king should, afterreflection, levy taxes in such a way that he and the person who laboursto produce the article taxed may both share the value. The king shouldnot, by his thirst, destroy his own foundations as also those of others.He should always avoid those acts in consequence of which he may becomean object of hatred to his people. Indeed, by acting in this way he maysucceed in winning popularity. The subjects hate that king who earns anotoriety for voraciousness of appetite (in the matter of taxes andimposts). Whence can a king who becomes an object of hatred haveprosperity? Such a king can never acquire what is for his good. A kingwho is possessed of sound intelligence should milk his kingdom after theanalogy of (men acting in the matter of) calves. If the calf be permittedto suck, it grows strong, O Bharata, and bears heavy burthens. If, on theother hand, O Yudhishthira, the cow be milked too much, the calf becomeslean and fails to do much service to the owner. Similarly, if the kingdombe drained much, the subjects fail to achieve any act that is great. Thatking who protects his kingdom himself and shows favour to his subjects(in the matter of taxes and imposts) and supports himself upon what iseasily obtained, succeeds in earning many grand results. Does not theking then obtain wealth sufficient for enabling him to cope with hiswants?[252] The entire kingdom, in that case, becomes to him histreasury, while that which is his treasury becomes his bed chamber. Ifthe inhabitants of the cities and the provinces be poor, the king should,whether they depend upon him immediately or mediately, show themcompassion to the best of his power. Chastising all robbers that infestthe outskirts, the king should protect the people of his villages andmake them happy. The subjects, in the case, becoming sharers of theking’s weal and woe, feel exceedingly gratified with him. Thinking, inthe first instance, of collecting wealth, the king should repair to thechief centres of his kingdom one after another and endeavour to inspirehis people with fright. He should say unto them, ‘Here, calamitythreatens us. A great danger has arisen in consequence of the acts of thefoe. There is every reason, however, to hope that the danger will passaway, for the enemy, like a bamboo that has flowered, will very soon meetwith destruction. Many foes of mine, having risen up and combined with alarge number of robbers, desire to put our kingdom into difficulties, formeeting with destruction themselves. In view of this great calamityfraught with dreadful danger, I solicit your wealth for devising themeans of your protection. When the danger passes away, I will give youwhat I now take. Our foes, however, will not give back what they (ifunopposed) will take from you by force. On the other hand (if unopposed),they will even slay all your relatives beginning with your very spouses.You certainly desire wealth for the sake of your children and wives. I amglad at your prosperity, and I beseech you as I would my own children. Ishall take from you what it may be within your power to give me. I do notwish to give pain to any one. In seasons of calamity, you should, likestrong bulls, bear such burthens. In seasons of distress, wealth shouldnot be so dear to you. A king conversant with the considerations relatingto Time should, with such agreeable, sweet, and complimentary words, sendhis agents and collect imposts from his people. Pointing out to them thenecessity of repairing his fortifications and of defraying the expensesof his establishment and other heads, inspiring them with the fear offoreign invasion, and impressing them with the necessity that exists forprotecting them and enabling them to ensure the means of living in peace,the king should levy imposts upon the Vaisyas of his realm. If the kingdisregards the Vaisyas, they become lost to him, and abandoning hisdominions remove themselves to the woods. The king should, therefore,behave with leniency towards them. The king, O son of Pritha, shouldalways conciliate and protect the Vaisyas, adopt measures for inspiringthem with a sense of security and for ensuring them in the enjoyment ofwhat they possess, and always do what is agreeable to them. The king, OBharata, should always act in such a way towards the Vaisyas that theirproductive powers may be enhanced. The Vaisyas increase the strength of akingdom, improve its agriculture, and develop its trade. A wise king,therefore, should always gratify them. Acting with heedfulness andleniency, he should levy mild imposts upon them. It is always easy tobehave with goodness towards the Vaisyas. There is nothing productive ofgreater good to a kingdom, O Yudhishthira, then the adoption of suchbehaviour towards the Vaisyas of the realm.'”