Chapter 174

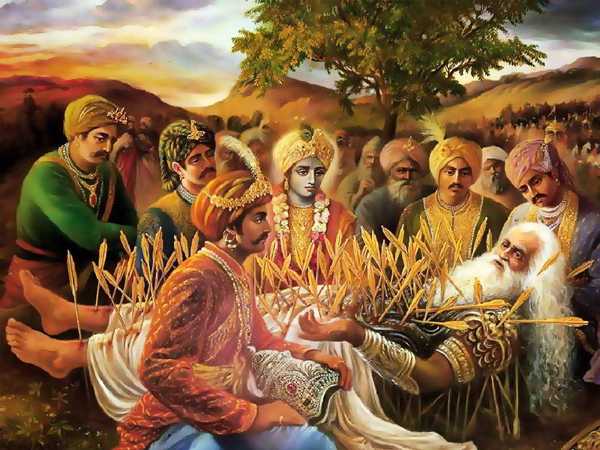

“YUDHISHTHIRA SAID, ‘THOU hast, O grandsire, discoursed upon theauspicious duties (of person in distress) connected with the duties ofkings. It behoveth thee now, O king, to tell me those foremost of dutieswhich belong to those who lead the (four) modes of life.’

“Bhishma said, ‘Religion hath many doors. The observance of (the dutiesprescribed by) religion can never be futile. Duties have been laid downwith respect to every mode of life. (The fruits of those duties areinvisible, being attainable in the next world.) The fruits, however, ofPenance directed towards the soul are obtainable in this world.[500]Whatever be the object to which one devotes oneself, that object, OBharata, and nothing else, appears to one as the highest of acquisitionsfraught with the greatest of blessings. When one reflects properly (one’sheart being purified by such reflection), one comes to know that thethings of this world are as valueless as straw. Without doubt, one isthen freed from attachment in respect of those things. When the world, OYudhishthira, which is full of defects, is so constituted, every man ofintelligence should strive for the attainment of the emancipation of hissoul.’

“Yudhishthira said, ‘Tell me, O grandsire, by what frame of soul shouldone kill one’s grief when one loses one’s wealth, or when one’s wife, orson, or sire, dies.’

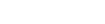

“Bhishma said, ‘When one’s wealth is lost, or one’s wife or son or sireis dead, one certainly says to oneself ‘Alas, this is a great sorrow!’But then one should, by the aid of reflection, seek to kill that sorrow.In this connection is cited the old story of the speech that a regeneratefriend of his, coming to Senajit’s court, made to that king. Beholdingthe monarch agitated with grief and burning with sorrow on account of thedeath of his son, the Brahmana addressed that ruler of very cheerlessheart and said these words, ‘Why art thou stupefied? Thou art without anyintelligence. Thyself an object of grief, why dost thou grieve (forothers)? A few days hence others will grieve for thee, and in their turnthey will be grieved for by others. Thyself, myself, and others who waitupon thee, O king, shall all go to that place whence all of us have come.’

“Senajit said, ‘What is that intelligence, what is that penance, Olearned Brahmana, what is that concentration of mind, O thou that hastwealth of asceticism, what is that knowledge, and what is that learning,by acquiring which thou dost not yield to sorrow?’

“The Brahmana said, ‘Behold, all creatures,–the superior, the middling,and the inferior,–in consequence of their respective acts, are entangledin grief. I do not regard even my own self to be mine. On the other hand,I regard the whole world to be mine. I again think that all this (which Isee) is as much mine as it belongs to others. Grief cannot approach me inconsequence of this thought. Having acquired such an understanding, I donot yield either to joy or to grief. As two pieces of wood floating onthe ocean come together at one time and are again separated, even such isthe union of (living) creatures in this world. Sons, grandsons, kinsmen,relatives are all of this kind. One should never feel affection for them,for separation with them is certain. Thy son came from an invisibleregion. He has departed and become invisible. He did not know thee. Thoudidst not know him. Who art thou and for whom dost thou grieve? Grievearises from the disease constituted by desire. Happiness again resultsfrom the disease of desire being cured. From joy also springs sorrow, andhence sorrow arises repeatedly. Sorrow comes after joy, and joy aftersorrow. The joys and sorrows of human beings are revolving on a wheel.After happiness sorrow has come to thee. Thou shalt again have happiness.No one suffers sorrow for ever, and no one enjoys happiness for ever. Thebody is the refuge of both sorrow and happiness.[501] Whatever acts anembodied creature does with the aid of his body, the consequence thereofhe has to suffer in that body. Life springs with the springing of thebody into existence. The two exist together, and the two perishtogether.[502] Men of uncleansed souls, wedded to worldly things byvarious bonds, meet with destruction like embankments of sand in water.Woes of diverse kinds, born of ignorance, act like pressers of oil-seeds,for assailing all creatures in consequence of their attachments. Thesepress them like oil-seeds in the oil-making machine represented by theround of rebirths (to which they are subject). Man, for the sake of hiswife (and others), commits numerous evil acts, but suffers singly diversekinds of misery both in this and the next world. All men, attached tochildren and wives and kinsmen and relatives, sink in the miry sea ofgrief like wild elephants, when destitute of strength, sinking in a miryslough. Indeed. O lord, upon loss of wealth or son or kinsmen orrelatives, man suffers great distress, which resembles as regards itspower of burning, a forest conflagration. All this, viz., joy and grief,existence and non-existence, is dependent upon destiny. One havingfriends as one destitute of friends, one having foes as one destitute offoes, one having wisdom as one destitute of wisdom, each and every oneamongst these, obtains happiness through destiny. Friends are not thecause of one’s happiness. Foes are not the cause of one’s misery. Wisdomis not competent to bring an accession of wealth; nor is wealth competentto bring an accession of happiness. Intelligence is not the cause ofwealth, nor is stupidity the cause of penury. He only that is possessedof wisdom, and none else, understands the order of the world. Amongst theintelligent, the heroic, the foolish, the cowardly, the idiotic, thelearned, the weak, or the strong, happiness comes to him for whom it isordained. Among the calf, the cowherd that owns her, and the thief, thecow indeed belongs to him who drinks her milk.[503] They whoseunderstanding is absolutely dormant, and they who have attained to thatstate of the mind which lies beyond the sphere of the intellect, succeedin enjoying happiness. Only they that are between the two classes, suffermisery.[504] They that are possessed of wisdom delight in the twoextremes but not in the states that are intermediate. The sages have saidthat the attainment of any of these two extremes constitutes happiness.Misery consists in the states that are intermediate between the two.[505]They who have succeeded in attaining to real felicity (which samadhi canbring), and who have become free from the pleasures and pains of thisworld, and who are destitute of envy, are never agitated by either theaccession of wealth or its loss. They who have not succeeded in acquiringthat intelligence which leads to real felicity, but who have transcendedfolly and ignorance (by the help of a knowledge of the scriptures), giveway to excessive joy and excessive misery. Men destitute of all notionsof right or wrong, insensate with pride and with success over others,yield to transports of delight like the gods in heaven.[506] Happinessmust end in misery. Idleness is misery; while cleverness (in action) isthe cause of happiness. Affluence and prosperity dwell in one possessedof cleverness, but not in one that is idle. Be it happiness or be itmisery, be it agreeable or be it disagreeable, what comes to one shouldbe enjoyed or endured with an unconquered heart. Every day a thousandoccasions for sorrow, and hundred occasions for fear assail the man ofignorance and folly but not the man that is possessed of wisdom. Sorrowcan never touch the man that is possessed of intelligence, that hasacquired wisdom, that is mindful of listening to the instructions of hisbetters, that is destitute of envy, and that is self-restrained. Relyingupon such an understanding, and protecting his heart (from the influencesof desire and the passions), the man of wisdom should conduct himselfhere. Indeed, sorrow is unable to touch him who is conversant with thatSupreme Self from which everything springs and unto which everythingdisappears.[507] The very root of that for which grief, or heartburning,or sorrow is felt or for which one is impelled to exertion, should, evenif it be a part of one’s body, be cast off. That object, whatever it maybe in respect of which the idea of meum is cherished, becomes a source ofgrief and heart-burning. Whatever objects, amongst things that aredesired, are cast off become sources of happiness. The man that pursuesobjects of desire meets with destruction in course of the pursuit.Neither the happiness that is derived from a gratification of the sensesnor that great felicity which one may enjoy in heaven, approaches to evena sixteenth part of the felicity which arises from the destruction of alldesires. The acts of a former life, right or wrong, visit, in theirconsequences, the wise and the foolish, the brave and the timid. It iseven thus that joy and sorrow, the agreeable and the disagreeable,continually revolve (as on a wheel) among living creatures. Relying uponsuch an understanding, the man of intelligence and wisdom lives at ease.A person should disregard all his desires, and never allow his wrath toget the better of him. This wrath springs in the heart and grows thereinto vigour and luxuriance. This wrath that dwells in the bodies of menand is born in their minds, is spoken of by the wise as Death. When aperson succeeds in withdrawing all his desires like a tortoisewithdrawing all its limbs, then his soul, which is self-luminous,succeeds in looking into itself.[508] That object, whatever it may be, inrespect of which the idea of meum is cherished, becomes a source of griefand heart-burning.[509] When a person himself feels no fear, and isfeared by no one, when he cherishes no desire and no aversion, he is thensaid to attain to the state of Brahma. Casting off both truth andfalsehood, grief and joy, fear and courage, the agreeable and thedisagreeable, thou mayst become of tranquil soul. When a person abstainsfrom doing wrong to any creature, in thought, word, or deed, he is thensaid to attain to a state of Brahma. True happiness is his who can castoff that thirst which is incapable of being cast off by the misguided,which does not decay with decrepitude, and which is regarded as a fataldisease. In this connection, O king, are heard the verses sung by Pingalaabout the manner in which she had acquired eternal merit even at a timethat had been very unfavourable. A fallen woman of the name of Pingala,having repaired to the place of assignation, was denied the company ofher lover through an accident. At that time of great misery, shesucceeded in acquiring tranquillity of soul.’

“Pingala said, ‘Alas, I have for many long years lived, all the whileovercome by frenzy, by the side of that Dear Self in whom there isnothing but tranquillity. Death has been at my door. Before this, I didnot, however approach that Essence of Purity. I shall cover this house ofone column and nine doors (by means of true Knowledge).[510] What womanis there that regards that Supreme Soul as her dear lord, even when Hecomes near?[511] I am now awake. I have been roused from the sleep ofignorance. I am no longer influenced by desire. Human lovers, who arereally the embodied forms of hell, shall no longer deceive me byapproaching me lustfully. Evil produces good through the destiny or theacts of a former life. Roused (from the sleep of ignorance), I have castoff all desire for worldly objects. I have acquired a complete masteryover my senses. One freed from desire and hope sleeps in felicity.Freedom from every hope and desire is felicity. Having driven off desireand hope, Pingala sleeps in felicity.’

“Bhishma continued, ‘Convinced with these and other words uttered by thelearned Brahmana, king Senajit (casting off his grief), experienceddelight and became very happy.'”