Chapter 267

“Yudhishthira said, ‘How, indeed, should the king protect his subjectswithout injuring anybody. I ask thee this, O grandsire, tell me, Oforemost of good men!’

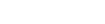

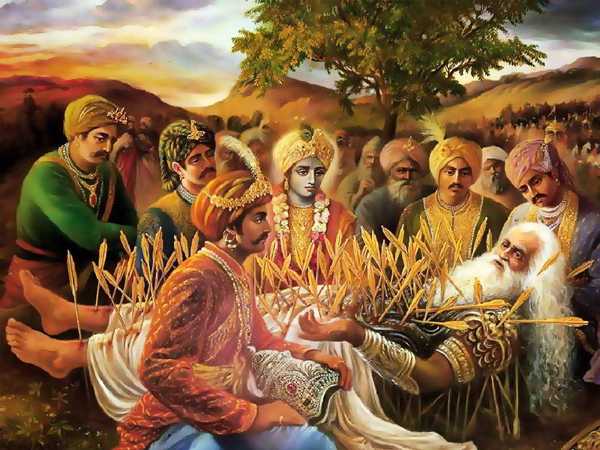

“Bhishma said, ‘In this connection is cited the old narrative of theconversation between Dyumatsena and king Satyavat. We have heard thatupon a certain number of individuals having been brought out forexecution at the command of his sire (Dyumatsena), prince Satyavat saidcertain words that had never before been said by anybody else.[1212]’Sometimes righteousness assumes the form of iniquity, and iniquityassumes the form of righteousness. It can never be possible that thekilling of individuals can ever be a righteous act.’

“Dyumatsena said, ‘If the sparing of those that deserve to be slain berighteousness, if robbers be spared, O Satyavat, then all distinctions(between virtue and vice) would disappear. ‘This is mine’,–‘This (other)is not his’–ideas like these (with respect to property) will not (if thewicked be not punished) prevail in the Kali age. (If the wicked be notpunished) the affairs of the world will come to a deadlock. If thouknowest how the world may go on (without punishing the wicked), thendiscourse to me upon it.’

“Satyavat said, ‘The three other orders (viz., the Kshatriyas, Vaisyas,and Sudras) should be placed under the control of the Brahmanas. If thosethree orders be kept within the bonds of righteousness, then thesubsidiary classes (that have sprung from intermixture) will imitate themin their practices. Those amongst them that will transgress (the commandsof the Brahmanas) shall be reported to the king.–‘This one heeds not mycommands,’–upon such a complaint being preferred by a Brahmana, the kingshall inflict punishment upon the offender. Without destroying the bodyof the offender the king should do that unto him which is directed by thescriptures. The king should not act otherwise, neglecting to reflectproperly upon the character of the offence and upon the science ofmorality. By slaying the wicked, the king (practically) slays a largenumber of individuals that are innocent. Behold, by slaying a singlerobber, his wife, mother, father and children are all slain (because theybecome deprived of the means of life). When injured by a wicked person,the king should, therefore, reflect deeply on the question ofchastisement.[1213] Sometimes a wicked man is seen to imbibe goodbehaviour from a righteous person. Then again from persons that arewicked, good children may be seen to spring. The wicked, therefore,should not be torn up by the roots. The extermination of the wicked isnot consistent with eternal practice. By smiting them gently they may bemade to expiate their offences. By depriving them of all their wealth, bychains and immurement in dungeons, by disfiguring them (they may be madeto expiate their guilt). Their relatives should not be persecuted by theinfliction of capital sentences on them. If in the presence of thePurohita and others,[1214] they give themselves up to him from desire ofprotection, and swear, saying, ‘O Brahmana, we shall never again commitany sinful act,’ they would then deserve to be let off without anypunishment. This is the command of the Creator himself. Even the Brahmanathat wears a deer-skin and the wand of (mendicancy) and has his headshaved, should be punished (when he transgresses).[1215] If great mentransgress, their chastisement should be proportionate to theirgreatness. As regards them that offend repeatedly, they do not deserve tobe dismissed without punishment as on the occasion of their firstoffence.'[1216] “Dyumatsena said, ‘As long as those barriers within whichmen should be kept are not transgressed, so long are they designated bythe name of Righteousness. If they who transgressed those, barriers werenot punished with death, those barriers would soon be destroyed. Men ofremote and remoter times were capable of being governed with ease.[1217]They were very truthful (in speech and conduct). They were littledisposed to disputes and quarrels. They seldom gave way to anger, or, ifthey did, their wrath never became ungovernable. In those days the merecrying of fie on offenders was sufficient punishment. After this came thepunishment represented by harsh speeches or censures. Then followed thepunishment of fines and forfeitures. In this age, however, the punishmentof death has become current. The measure of wickedness has increased tosuch an extent that by slaying one others cannot be restrained.[1218] Therobber has no connection with men, with the deities, with the Gandharvas,and with the Pitris. What is he to whom? He is not anybody to any one.This is the declaration of the Srutis.[1219] The robber takes away theornaments of corpses from cemeteries, and swearing apparel from menafflicted by spirits (and, therefore, deprived of senses). That man is afool who would make any covenant with those miserable wretches or exactany oath from them (for relying upon it).'[1220]

“Satyavat said, ‘If thou dost not succeed in making honest men of thoserogues and in saving them by means unconnected with slaughter, do thouthen exterminate them by performing some sacrifice.[1221] Kings practisesevere austerities for the sake of enabling their subjects go onprosperously in their avocations. When thieves and robbers multiply intheir kingdoms they become ashamed.. They, therefore, betake themselvesto penances for suppressing thefts and robberies and making theirsubjects live happily. Subjects can be made honest by being onlyfrightened (by the king). Good kings never slay the wicked from motivesof retribution. (On the other hand, if they slay, they slay insacrifices, when the motive is to do good to the slain), Good kingsabundantly succeed in ruling their subjects properly with the aid of goodconduct (instead of cruel or punitive inflictions). If the king actsproperly, the superior subjects imitate him. The inferior people, againin their turn, imitate their immediate superiors. Men are so constitutedthat they imitate those whom they regard as their superiors.[1222] Thatking who, without restraining himself, seeks to restrain others (fromevil ways) becomes an object of laughter with all men in consequence ofhis being engaged in the enjoyment of all worldly pleasures as a slave ofhis senses. That man who, through arrogance or error of judgment, offendsagainst the king in any way, should be restrained by every means. It isby this way that he is prevented from committing offences anew. The kingshould first restrain his own self if he desires to restrain others thatoffend. He should punish heavily (if necessary) even friends and nearrelatives. In that kingdom where a vile offender does not meet with heavyafflictions, offences increase and righteousness decreases without doubt.Formerly, a Brahmana. endued with clemency and possessed of learning,taught me this. Verily, to this effect, O sire, I have been instructed byalso our grandsire of olden days, who gave such assurances ofharmlessness to people, moved by pity. Their words were, ‘In the Kritaage, kings should rule their subjects by adopting ways that are entirelyharmless. In the Treta age, kings conduct themselves according to waysthat conform with righteousness fallen away by a fourth from its fullcomplement. In the Dwapara age, they proceed according to ways conformingwith righteousness fallen away by a moiety, and in the age that follows,according to ways conforming with righteousness fallen away bythree-fourth. When the Kati age sets in, through the wickedness of kingsand in consequence of the nature of the epoch itself, fifteen parts ofeven that fourth portion of righteousness disappear, a sixteenth portionthereof being all that then remains of it. If, O Satyavat, by adoptingthe method first mentioned (viz., the practice of harmlessness),confusion sets in, the king, considering the period of human life, thestrength of human beings, and the nature of the time that has come,should award punishments.[1223] Indeed, Manu, the son of the Self-born,has, through compassion for human beings, indicated the way by means ofwhich men may adhere to knowledge (instead of harmfulness) for the sakeof emancipation.'”[1224]