Chapter 266

“Yudhishthira said, ‘Thou, O grandsire, art our highest preceptor in thematter of all acts that are difficult of accomplishment (in consequenceof the commands of superiors on the one hand and the cruelty that isinvolved in them on the other). I ask, how should one judge of an act inrespect of either one’s obligation to do it or of abstaining from it? Isit to be judged speedily or with delay?’

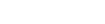

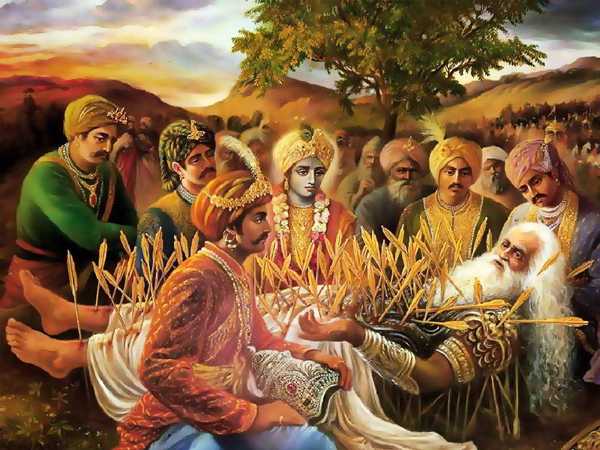

“Bhishma said, ‘In this connection is cited the old story of whatoccurred with respect to Chirakarin born in the race of Angirasa. Twiceblessed be the man that reflects long before he acts. One that reflectslong before he acts is certainly possessed of great intelligence. Such aman never offends in respect of any act. There was once a man of greatwisdom, of the name of Chirakarin, who was the son of Gautama. Reflectingfor a long time upon every consideration connected with proposed acts, heused to do all he had to do. He came to be called by the name ofChirakarin because he used to reflect long upon all matters, to remainawake for a long time, to sleep for a long time, and to take a long timein setting himself to the accomplishment of such acts as he accomplished.The clamour of being an idle man stuck to him. He was also regarded as afoolish person, by every person of a light understanding and destitute offoresight. On a certain occasion, witnessing an act of great fault in hiswife, the sire Gautama passing over his other children, commanded inwrath this Chirakarin, saying, ‘Slay thou this woman.’ Having said thesewords without much reflection, the learned Gautama, that foremost ofpersons engaged in the practice of Yoga, that highly blessed ascetic,departed for the woods. Having after a long while assented to it, saying,’So be it,’ Chirakarin, in consequence of his very nature, and owing tohis habit of never accomplishing any act without long reflection, beganto think for a long while (upon the propriety or otherwise of what he wascommanded by his sire to do). How shall I obey the command of my sire andyet how avoid slaying my mother? How shall I avoid sinking, like a wickedperson, into sin in this situation in which contradictory obligations aredragging me into opposite directions? Obedience to the commands of thesire constitutes the highest merit. The protection of the mother again isa clear duty. The status of a son is fraught with dependence. How shall Iavoid being afflicted by sin? Who is there that can be happy after havingslain a woman, especially his mother? Who again can obtain prosperity andfame by disregarding his own sire? Regard for the sire’s behest isobligatory. The protection of my mother is equally a duty. How shall I soframe my conduct that both obligations may be discharged? The fatherplaces his own self within the mother’s womb and takes birth as the son,for continuing his practices, conduct, name and race. I have beenbegotten as a son by both my mother and my father. Knowing as I do my ownorigin, why should I not have this knowledge (of my relationship withboth of them)? The words uttered by the sire while performing the initialrite after birth, and those that were uttered by him on the occasion ofthe subsidiary rite (after the return from the preceptor’s abode) aresufficient (evidence) for settling the reverence due to him and indeed,confirm the reverence actually paid to him.[1203] In consequence of hisbringing up the son and instructing him, the sire is the son’s foremostof superiors and the highest religion. The very Vedas lay it down ascertain that the son should regard what the sire says as his highestduty. Unto the sire the son is only a source of joy. Unto the son,however, the sire is all in all. The body and all else that the son ownshave the sire alone for their giver. Hence, the behests of the sireshould be obeyed without ever questioning them in the least. The verysins of one that obeys one’s sire are cleansed (by such obedience). Thesire is the giver of all articles of food, of instructions in the Vedas,and of all other knowledge regarding the world. (Prior to the son’sbirth) the sire is the performer of such rites as Garbhadhana andSimantonnayana.[1204] The sire is religion. The sire is heaven. The sireis the highest penance. The sire being gratified, all the deities aregratified. Whatever words are pronounced by the sire become blessingsthat attach to the son. The words expressive of joy that the sire utterscleanse the son of all his sins. The flower is seen to fall away from thestalk. The fruit is seen to fall away from the tree. But the sire,whatever his distress, moved by parental affection, never abandons theson. These then are my reflections upon the reverence due from the son tothe sire. Unto the son the sire is not an ordinary object. I shall nowthink upon (what is due to) the mother. Of this union of the five(primal) elements in me due to my birth as a human being, the mother isthe (chief) cause as the firestick of fire.[1205] The mother is as thefire-stick with respect to the bodies of all men. She is the panacea forall kinds of calamities. The existence of the mother invests one withprotection; the reverse deprives one of all protection. The man who,though divested of prosperity, enters his house, uttering the words, ‘Omother!’–hath not to indulge in grief. Nor doth decrepitude ever assailhim. A person whose mother exists, even if he happens to be possessed ofsons and grandsons and even if he counts a hundred years, looks like achild of but two years of age. Able or disabled, lean or robust, the sonis always protected by the mother. None else, according to the ordinance,is the son’s protector. Then doth the son become old, then doth he becomestricken with grief, then doth the world look empty in his eyes, when hebecomes deprived of his mother. There is no shelter (protection againstthe sun) like the mother. There is no refuge like the mother. There is nodefence like the mother. There is no one so dear as the mother. Forhaving borne him in her womb the mother is the son’s Dhatri. For havingbeen the chief cause of his birth, she is his Janani. For having nursedhis young limbs into growth, she is called Amva. For bringing forth achild possessed of courage she is called Virasu. For nursing and lookingafter the son she is called Sura. The mother is one’s own body. Whatrational man is there that would slay his mother, to whose care alone itis due that his own head did not lie on the street-side like a dry gourd?When husband and wife unite themselves for procreation, the desirecherished with respect to the (unborn) son are cherished by both, but inrespect of their fruition more depends upon the mother than on thesire.[1206] The mother knows the family in which the son is born and thefather who has begotten him. From the moment of conception the motherbegins to show affection to her child and takes delight in her. (For thisreason, the son should behave equally towards her). On the other hand,the scriptures declare that the offspring belongs to the father alone. Ifmen, after accepting the hands of wives in marriage and pledgingthemselves to earn religious merit without being dissociated from them,seek congress with other people’s wives, they then cease to be worthy ofrespect.[1207] The husband, because he supports the wife, is calledBhartri, and, because he protects her, he is on that account called Pati.When these two functions disappear from him, he ceases to be both Bhartriand Pati.[1208] Then again woman can commit no fault. It is man only thatcommits faults. By perpetrating an act of adultery, the man only becomesstained with guilt.[1209] It has been said that the husband is thehighest object with the wife and the highest deity to her. My mother gaveup her sacred person to one that came to her in the form and guise of herhusband. Women can commit no fault. It is man who becomes stained withfault. Indeed, in consequence of the natural weakness of the sex asdisplayed in every act, and their liability to solicitation, women cannotbe regarded as offenders. Then again the sinfulness (in this case) isevident of Indra himself who (by acting in the way he did) caused therecollection of the request that had been made to him in days of yore bywoman (when a third part of the sin of Brahmanicide of which Indrahimself was guilty was cast upon her sex). There is no doubt that mymother is innocent. She whom I have been commanded to slay is a woman.That woman is again my mother. She occupies, therefore, a place ofgreater reverence. The very beasts that are irrational know that themother is unslayable. The sire must be known to be a combination of allthe deities together. To the mother, however, attaches a combination ofall mortal creatures and all the deities.[1210]–In consequence of hishabit of reflecting long before acting, Gautama’s son Chirakarin, byindulging in those reflections, passed a long while (withoutaccomplishing the act he had been commanded by his sire to accomplish).When many days had expired, his sire Gautama’s returned. Endued withgreat wisdom, Medhatithi of Gautama’s race, engaged in the practice ofpenances, came back (to his retreat), convinced, after having reflectedfor that long time, of the impropriety of the chastisement he hadcommanded to be inflicted upon his wife. Burning with grief and sheddingcopious tears, for repentance had come to him in consequence of thebeneficial effects of that calmness of temper which is brought about by aknowledge of the scriptures, he uttered these words, ‘The lord of thethree worlds, viz., Purandara, came to my retreat, in the guise of aBrahmana asking for hospitality. He was received by me with (proper)words, and honoured with a (proper) welcome, and presented in due formwith water to wash his feet and the usual offerings of the Arghya. I alsogranted him the rest he had asked for. I further told him that I hadobtained a protector in him. I thought that such conduct on my part wouldinduce him to behave towards me as a friend. When, however,notwithstanding all this, he misbehaved himself, my wife Ahalya could notbe regarded to have committed any fault. It seems that neither my wife,nor myself, nor Indra himself who while passing through the sky hadbeheld my wife (and become deprived of his senses by her extraordinarybeauty), could be held to have offended. The blame really attaches to thecarelessness of my Yoga puissance.[1211] The sages have said that allcalamities spring from envy, which, in its turn, arises from error ofjudgment. By that envy, also, I have been dragged from where I was andplunged into an ocean of sin (in the form of wife-slaughter). Alas, Ihave slain a woman,–a woman that is again my wife–one, that is, who, inconsequence of her sharing her lord’s calamities came to be called by thename of Vasita,–one that was called Bharya owing to the obligation I wasunder of supporting her. Who is there that can rescue me from this sin?Acting heedlessly I commanded the high-souled Chirakarin (to slay thatwife of mine). If on the present occasion he proves true to his name thenmay he rescue me from this guilt. Twice blessed be thou, O Chirakaraka!If on this occasion thou hast delayed accomplishing the work, then artthou truly worthy of thy name. Rescue me, and thy mother, and thepenances I have achieved, as also thy own self, from grave sins. Be thoureally a Chirakaraka today! Ordinarily, in consequence of thy greatwisdom thou takest a long time for reflection before achieving any act.Let not thy conduct be otherwise today! Be thou a true Chirakaraka today.Thy mother had expected thy advent for a long time. For a long time didshe bear thee in her womb. O Chirakaraka, let thy habit of reflectinglong before acting be productive of beneficial results today. Perhaps, myson Chirakaraka is delaying today (to achieve my bidding) in view of thesorrow it would cause me (to see him execute that bidding). Perhaps, heis sleeping over that bidding, bearing it in his heart (without anyintention of executing it promptly). Perhaps, he is delaying, in view ofthe grief it would cause both him and me, reflecting upon thecircumstances of the case.’ Indulging in such repentance, O king, thegreat Rishi Gautama then beheld his son Chirakarin sitting near him.Beholding his sire come back to their abode, the son Chirakarin,overwhelmed with grief, cast away the weapon (he had taken up) and bowinghis head began to pacify Gautama. Observing his son prostrated before himwith bent head, and beholding also his wife almost petrified with shame,the Rishi became filled with great joy. From that time the highsouledRishi, dwelling in that lone hermitage, did not live separately from hisspouse or his heedful son. Having uttered the command that his wifeshould be slain he had gone away from his retreat for accomplishing somepurpose of his own. Since that time his son had stood in an humbleattitude, weapon in hand, for executing that command on his mother.Beholding that his son prostrated at his feet, the sire thought that,struck with fear, he was asking for pardon for the offence he hadcommitted in taking up a weapon (for killing his own mother). The sirepraised his son for a long time, and smelt his head for a long time, andfor a long time held him in a close embrace, and blessed him, utteringthe words, ‘Do thou live long!’ Then, filled with joy and contented withwhat had occurred, Gautama, O thou of great wisdom, addressed his son andsaid these words, ‘Blessed be thou, O Chirakaraka! Do thou always reflectlong before acting. By thy delay in accomplishing my bidding thou hasttoday made me happy for ever.’ That learned and best of Rishis thenuttered these verses upon the subject of the merits of such cool men asreflect for a long time before setting their hands to any action. If thematter is the death of a friend, one should accomplish it after a longwhile. If it is the abandonment of a project already begun, one shouldabandon it after a long while. A friendship that is formed after a longexamination lasts for a long time. In giving way to wrath, tohaughtiness, to pride, to disputes, to sinful acts, and in accomplishingall disagreeable tasks he that delays long deserves applause. When theoffence is not clearly proved against a relative, a friend, a servant, ora wife, he that reflects long before inflicting the punishment isapplauded.’ Thus, O Bharata, was Gautama pleased with his son, O thou ofKuru’s race, for that act of delay on the latter’s part in doing theformer’s bidding. In all acts a man should, in this way, reflect for along time and then settle what he should do. By conducting himself inthis way one is sure to avoid grief for a long time. That man who nevernurses his wrath for a long while, who reflects for a long time beforesetting himself to the performance of any act, never does any act whichbrings repentance. One should wait for a long while upon those that areaged, and sitting near them show them reverence. One should attend toone’s duties for a long time and be engaged for a long while inascertaining them. Waiting for a long time upon those that are learned,are reverentially serving for a long time those that are good inbehaviour, and keeping one’s soul for a long while under properrestraint, one succeeds in enjoying the respect of the world for a longtime. One engaged in instructing others on the subject of religion andduty, should, when asked by another for information on those subjects,take a long time to reflect before giving an answer. He may then avoidindulging in repentance (for returning an incorrect answer whosepractical consequences may lead to sin).–As regards Gautama of austerepenances, that Rishi, having adored the deities for a long while in thatretreat of his, at last ascended to heaven with his son.'”