Chapter 141

“Yudhishthira said, ‘When the high righteousness suffers decay and istransgressed by all, when unrighteousness becomes righteousness, andrighteousness assumes the form of its reverse, when all wholesomerestraints disappear, and all truths in respect of righteousness aredisturbed and confounded, when people are oppressed by kings and robbers,when men of all the four modes of life become stupefied in respect oftheir duties, and all acts lose their merit, when men see cause of fearon every direction in consequence of lust and covetousness and folly,when all creatures cease to trust one another, when they slay one anotherby deceitful means and deceive one another in their mutual dealings, whenhouses are burnt down throughout the country, when the Brahmanas becomeexceedingly afflicted, when the clouds do not pour a drop of rain, whenevery one’s hand is turned against every one’s neighbour, when all thenecessaries of life fall under the power of robbers, when, indeed, such aseason of terrible distress sets in, by what means should a Brahmana livewho is unwilling to cast off compassion and his children? How, indeed,should a Brahmana maintain himself at such a time? Tell me this, Ograndsire! How also should the king live at such a time when sinfulnessovertakes the world? How, O scorcher of foes, should the king live sothat he might not fall away from both righteousness and profit?’

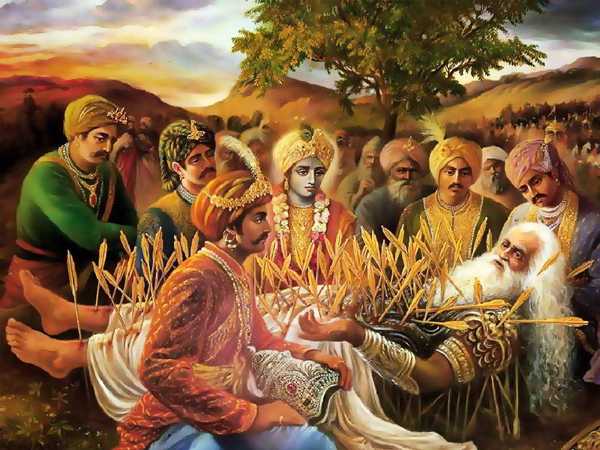

“Bhishma said, ‘O mighty-armed one, the peace and prosperity ofsubjects,[425] sufficiency and seasonableness of rain, disease, death andother fears, are all dependent on the king.[426] I have no doubt also inthis. O bull of Bharata’s race, that Krita, Treta, Dwapara, and Kali, asregards their setting in, are all dependent on the king’s conduct. Whensuch a season of misery as has been described by thee sets in, therighteous should support life by the aid of judgment. In this connectionis cited the old story of the discourse between Viswamitra and theChandala in a hamlet inhabited by Chandalas. Towards the end of Treta andthe beginning of Dwapara, a frightful drought occurred, extending overtwelve years, in consequence of what the gods had ordained. At that timewhich was the end of Treta and the commencement of Dwapara, when theperiod came for many creatures superannuated by age to lay down theirlives, the thousand-eyed deity of heaven poured no rain. The planetVrihaspati began to move in a retrograde course, and Soma abandoning hisown orbit, receded towards the south. Not even could a dew-drop be seen,what need then be said of clouds gathering together? The rivers allshrank into narrow streamlets. Everywhere lakes and wells and springsdisappeared and lost their beauty in consequence of that order of thingswhich the gods brought about. Water having become scarce, the places setup by charity for its distribution became desolate.[427] The Brahmanasabstained from sacrifices and recitation of the Vedas. They no longeruttered Vashats and performed other propitiatory rites. Agriculture andkeep of cattle were given up. Markets and shops were abandoned. Stakesfor tethering sacrificial animals disappeared. People no longer collecteddiverse kinds of articles for sacrifices. All festivals and amusementsperished. Everywhere heaps of bones were visible and every placeresounded with the shrill cries and yells of fierce creatures.[428] Thecities and towns of the earth became empty of inhabitants. Villages andhamlets were burnt down. Some afflicted by robbers, some by weapons, andsome by bad kings, and in fear of one another, began to fly away. Templesand places of worship became desolate. They that were aged were forciblyturned out of their houses. Kine and goats and sheep and buffaloes fought(for food) and perished in large numbers. The Brahmanas began to die onall sides. Protection was at an end. Herbs and plants were dried up. Theearth became shorn of all her beauty and exceedingly awful like the treesin a crematorium. In that period of terror, when righteousness wasnowhere, O Yudhishthira, men in hunger lost their senses and began to eatone another. The very Rishis, giving up their vows and abandoning theirfires and deities, and deserting their retreats in woods, began to wanderhither and thither (in search of food). The holy and great RishiViswamitra, possessed of great intelligence, wandered homeless andafflicted with hunger. Leaving his wife and son in some place of shelter,the Rishi wandered, fireless[429] and homeless, and regardless of foodclean and unclean. One day he came upon a hamlet, in the midst of aforest, inhabited by cruel hunters addicted to the slaughter of livingcreatures. The little hamlet abounded with broken jars and pots made ofearth. Dog-skins were spread here and there. Bones and skulls, gatheredin heaps, of boars and asses, lay in different places. Cloths strippedfrom the dead lay here and there, and the huts were adorned with garlandsof used up flowers.[430] Many of the habitations again were filled withsloughs cast off by snakes. The place resounded with the loud crowing ofcocks and hens and the dissonant bray of asses. Here and there theinhabitants disputed with one another, uttering harsh words in shrillvoices. Here and there were temples of gods bearing devices of owls andother birds. Resounding with the tinkle of iron bells, the hamletabounded with canine packs standing or lying on every side. The greatRishi Viswamitra, urged by pangs of hunger and engaged in search afterfood, entered that hamlet and endeavoured his best to find something toeat. Though the son of Kusika begged repeatedly, yet he failed to obtainany meat or rice or fruit or root or any other kind of food. He then,exclaiming, ‘Alas, great is the distress that has overtaken me!’ felldown from weakness in that hamlet of the Chandalas. The sage began toreflect, saying to himself, ‘What is best for me to do now?’ Indeed, Obest of kings, the thought that occupied him was of the means by which hecould avoid immediate death. He beheld, O king, a large piece of flesh,of a dog that had recently been slain with a weapon, spread on the floorof a Chandala’s hut. The sage reflected and arrived at the conclusionthat he should steal that meat. And he said unto himself, ‘I have nomeans now of sustaining life. Theft is allowable in a season of distressfor even an eminent person. It will not detract from his glory. Even aBrahmana for saving his life may do it. This is certain. In the firstplace one should steal from a low person. Failing such a person one maysteal from one’s equal. Failing an equal, one may steal from even aneminent and righteous man. I shall then, at this time when my life itselfis ebbing away, steal this meat. I do not see demerit in such theft. Ishall, therefore, rob this haunch of dog’s meat.’ Having formed thisresolution, the great sage Viswamitra laid himself down for sleep in thatplace where the Chandala was. Seeing some time after that the night hadadvanced and that the whole Chandala hamlet had fallen asleep, the holyViswamitra, quietly rising up, entered that hut. The Chandala who ownedit, with eyes covered with phlegm, was lying like one asleep. Ofdisagreeable visage, he said these harsh words in a broken and dissonantvoice.

“The Chandala said, ‘Who is there, engaged in undoing the latch? Thewhole Chandala hamlet is asleep. I, however, am awake and not asleep.Whoever thou art, thou art about to be slain.’ These were the harsh wordsthat greeted the sage’s ears. Filled with fear, his face crimson withblushes of shame, and his heart agitated by anxiety caused by that act oftheft which he had attempted, he answered, saying, ‘O thou that art blestwith a long life, I am Viswamitra. I have come here oppressed by thepangs of hunger. O thou of righteous understanding, do not slay me, ifthy sight be clear.’ Hearing these words of that great Rishi of cleansedsoul, the Chandala rose up in terror from his bed and approached thesage. Joining his palms from reverence and with eyes bathed in tears, headdressed Kusika’s son, saying, ‘What do you seek here in the night, OBrahmana?’ Conciliating the Chandala, Viswamitra said, ‘I am exceedinglyhungry and about to die of starvation. I desire to take away that haunchof dog’s meat. Being hungry, I have become sinful. One solicitous of foodhas no shame. It is hunger that is urging me to this misdeed. It is forthis that I desire to take away that haunch of dog’s meat. Mylife-breaths are languishing. Hunger has destroyed my Vedic lore. I amweak and have lost my senses. I have no scruple about clean or uncleanfood. Although I know that it is sinful, still I wish to take away thathaunch of dog’s meat. After I had filed to obtain any alms, havingwandered from house to house in this your hamlet, I set my heart uponthis sinful act of taking away this haunch of dog’s meat. Fire is themouth of the gods. He is also their priest. He should, therefore, takenothing save things that are pure and clean. At times, however, thatgreat god becomes a consumer of everything. Know that I have now becomeeven like him in that respect.’ Hearing these words of the great Rishi,the Chandala answered him, saying, ‘Listen to me. Having heard the wordsof truth that I say, act in such a way that thy religious merit may notperish. Hear, O regenerate Rishi, what I say unto thee about thy duty.The wise say that a dog is less clean than a jackal. The haunch, again,of a dog is a much worse part than other parts of his body. This was notwisely resolved by thee, therefore, O great Rishi, this act that isinconsistent with righteousness, this theft of what belongs to aChandala, this theft, besides, of food that is unclean. Blessed be thou,do thou look for some other means for preserving thy life. O great sage,let not thy penances suffer destruction in consequence of this thy strongdesire for dog’s meat. Knowing as thou dost the duties laid down in thescriptures, thou shouldst not do an act whose consequence is a confusionof duties.[431] Do not cast off righteousness, for thou art the foremostof all persons observant of righteousness.’ Thus addressed, O king, thegreat Rishi Viswamitra, afflicted by hunger, O bull of Bharata’s race,once more said, ‘A long time has passed away without my having taken anyfood. I do not see any means again for preserving my life. One should,when one is dying, preserve one’s life by any means in one’s powerwithout judging of their character. Afterwards, when competent, oneshould seek the acquisition of merit. The Kshatriyas should observe thepractices of Indra. It is the duty of the Brahmanas to behave like Agni.The Vedas are fire. They constitute my strength. I shall, therefore, eateven this unclean food for appeasing my hunger. That by which life may bepreserved should certainly be accomplished without scruple. Life isbetter than death. Living, one may acquire virtue. Solicitous ofpreserving my life, I desire, with the full exercise of my understanding,to eat this unclean food. Let me receive thy permission. Continuing tolive I shall seek the acquisition of virtue and shall destroy by penancesand by knowledge the calamities consequent on my present conduct, likethe luminaries of the firmament destroying even the thickest gloom.’

“The Chandala said, ‘By eating this food one (like thee) cannot obtainlong life. Nor can one (like thee) obtain strength (from such food), northat gratification which ambrosia offers. Do thou seek for some otherkind of alms. Let not thy heart incline towards eating dog’s meat. Thedog is certainly an unclean food to members of the regenerate classes.’

“Viswamitra said, ‘Any other kind of meat is not to be easily had duringa famine like this. Besides, O Chandala, I have no wealth (wherewith tobuy food). I am exceedingly hungry. I cannot move any longer. I amutterly hopeless. I think that all the six kinds of taste are to be foundin that piece of dog’s meat.’

“The Chandala said, ‘Only the five kinds of five-clawed animals are cleanfood for Brahmanas and Kshatriyas and Vaisyas, as laid down in thescriptures. Do not set thy heart upon what is unclean (for thee).’

“Viswamitra said, ‘The great Rishi Agastya, while hungry, ate up theAsura named Vatapi. I am fallen into distress. I am hungry. I shalltherefore, eat that haunch of dog’s meat.’

“The Chandala said, ‘Do thou seek some other alms. It behoves thee not todo such a thing. Verily, such an act should never be done by thee. Ifhowever, it pleases thee, thou mayst take away this piece of dog’s meat.’

“Viswamitra said, ‘They that are called good are authorities in mattersof duty. I am following their example. I now regard this dog’s haunch tobe better food than anything that is highly pure.’

“The Chandala said, ‘That which is the act of an unrighteous person cannever be regarded as an eternal practice. That which is an improper actcan never be a proper one. Do not commit a sinful act by deception.’

“Viswamitra said, ‘A man who is a Rishi cannot do what is sinful.[432] Inthe present case, deer and dog, I think, are same (both being animals). Ishall, therefore, eat this dog’s haunch.’

“The Chandala said, “Solicited by the Brahmanas, the Rishi (Agastya) didthat act. Under the circumstances it could not be a sin. That isrighteousness in which there is no sin. Besides, the Brahmanas, who arethe preceptors of three other orders, should be protected and preservedby every means.’

“Viswamitra said, ‘I am a Brahmana. This my body is a friend of mine. Itis very dear to me and is worthy of the highest reverence from me. It isfrom the desire of sustaining the body that the wish is entertained by meof taking away that dog’s haunch. So eager have I become that I have nolonger any fear of thee and thy fierce brethren.’

“The Chandala said, ‘Men lay down their lives but they still do not settheir hearts on food that is unclean. They obtain the fruition of alltheir wishes even in this world by conquering hunger. Do thou alsoconquer thy hunger and obtain those rewards.’

“Viswamitra said, ‘As regards myself, I am observant of rigid vows and myheart is set on peace. For preserving the root of all religious merit, Ishall eat food that is unclean. It is evident that such an act would beregarded as righteous in a person of cleansed soul. To a person, however,of uncleansed soul, the eating of dog’s flesh would appear sinful. Evenif the conclusion to which I have arrived be wrong, (and if I eat thisdog’s meat) I shall not, for that act, become one like thee.’

“The Chandala said, ‘It is my settled conclusion that I should endeavourmy best to restrain thee from this sin. A Brahmana by doing a wicked actfalls off from his high state. It is for this that I am reproving thee.’

“Viswamitra said, ‘Kine continue to drink, regardless of the croaking ofthe frogs. Thou canst lay no claim to what constitutes righteousness (andwhat not). Do not be a self-eulogiser.’

“The Chandala said, ‘I have become thy friend. For this reason only I ampreaching to thee. Do what is beneficial. Do not, from temptation, dowhat is sinful.’

“Viswamitra said, ‘If thou be a friend desirous of my happiness, do thouthen raise me up from this distress. In that case, relinquishing thisdog’s haunch, I may consider myself saved by the aid of righteousness(and not by that of sinfulness).’

“The Chandala said, ‘I dare not make a present of this piece of meat tothee, nor can I quietly suffer thee to rob me of my own food. If I givethee this meat and if thou take it, thyself being a Brahmana, both of uswill become liable to sink in regions of woe in the next world.’

“Viswamitra said, ‘By committing this sinful act today I shall certainlysave my life which is very sacred. Having saved my life, I shallafterwards practise virtue and cleanse my soul. Tell me which of thesetwo is preferable (to die without food, or save my life by taking thisfood that is unclean).’

“The Chandala said: ‘In discharging the duties that appertain to one’sorder or race, one’s own self is the best judge (of its propriety orimpropriety). Thou thyself knowest which of those two acts is sinful. Hewho would regard dog’s meat as clean food, I think, would in matters offood abstain from nothing!’

“Viswamitra said, ‘In accepting (an unclean present) or in eating(unclean food) there is sin. When one’s life, however, is in danger thereis no sin in accepting such a present or eating such food. Besides, theeating of unclean food, when unaccompanied by slaughter and deception andwhen the act will provoke only mild rebuke, is not matter of muchconsequence.’

“The Chandala said, ‘If this be thy reason for eating unclean food, it isthen clear thou dost not regard the Veda and Arya morality. Taught bywhat thou art going to do, I see, O foremost of Brahmanas, that there isno sin in disregarding the distinction between food that is clean andfood that is unclean.’

“Viswamitra said, ‘It is not seen that a person incurs a grave sin byeating (forbidden food). That one becomes fallen by drinking wine is onlya wordy precept (for restraining men from drinking). The other forbiddenacts (of the same species), whatever they be, in fact, every sin, cannotdestroy one’s merit.’

“The Chandala said, ‘That learned person who takes away dog’s meat froman unworthy place (like this), from an unclean wretch (like me), from onewho (like me) leads such a wicked life, commits an act that is opposed tothe behaviour of those that are called good. In consequence, again, ofhis connection with such a deed, he is certain to suffer the pangs ofrepentance.’

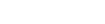

“Bhishma continued, ‘The Chandala, having said these words unto Kusika’sson, became silent. Viswamitra then, of cultivated understanding, tookaway that haunch of dog’s meat. The great ascetic having possessedhimself of that piece of dog’s meat for saving his life, took it awayinto the woods and wished with his wife to eat it. He resolved thathaving first gratified the deities according to due rites, he should theneat that haunch of dog’s meat at his pleasure. Igniting a fire accordingto the Brahma rites, the ascetic, agreeably to those rites that go by thename of Aindragneya, began himself to cook that meat into sacrificialCharu. He then, O Bharata, began the ceremonies in honour of the gods andthe Pitris, by dividing that Charu into as many portions as werenecessary, according to the injunctions of the scriptures, and byinvoking the gods with Indra at their head (for accepting their shares).Meanwhile, the chief of the celestials began to pour copiously. Revivingall creatures by those showers, he caused plants and herbs to grow oncemore. Viswamitra, however, having completed the rites in honour of thegods and the Pitris and having gratified them duly, himself ate thatmeat. Burning all his sins afterwards by his penances, the sage, after along time, acquired the most wonderful (ascetic) success. Even thus, whenthe end in view is the preservation of life itself, should a high-souledperson possessed of learning and acquainted with means rescue his owncheerless self, when fallen into distress, by all means in his power. Byhaving recourse to such understanding one should always preserve one’slife. A person, if alive, can win religious merit and enjoy happiness andprosperity. For this reason, O son of Kunti, a person of cleansed souland possessed of learning should live and act in this world, relying uponhis own intelligence in discriminating between righteousness and itsreverse.'”