Chapter 130

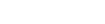

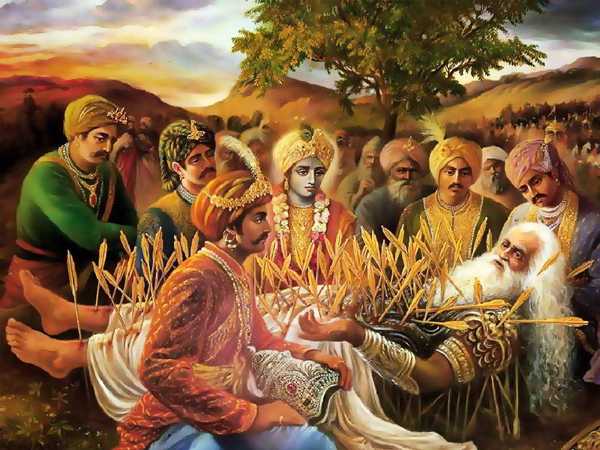

“Yudhishthira said, ‘What course of conduct should be adopted by a kingshorn of friends, having many enemies, possessed of an exhaustedtreasury, and destitute of troops, O Bharata! What, indeed, should be hisconduct when he is surrounded by wicked ministers, when his counsels areall divulged, when he does not see his way clearly before him, when heassails another kingdom, when he is engaged in grinding a hostilekingdom, and when though weak he is at war with a stronger ruler? What,indeed, should be the conduct of a king the affairs of whose kingdom areill-regulated, and who disregards the requirements of place and time, whois unable, in consequence of his oppressions, to bring about peace andcause disunion among his foes? Should he seek the acquisition of wealthby evil means, or should he lay down his life without seeking wealth?’

“Bhishma said, ‘Conversant as thou art with duties, thou hast, O bull ofBharata’s race, asked me a question relating to mystery (in connectionwith duties).[388] Without being questioned, O Yudhishthira, I could notventure to discourse upon this duty. Morality is very subtle. Oneunderstands it, O bull of Bharata’s race, by the aid of the texts ofscriptures. By remembering what one has heard and by practising goodacts, some one in some place may become a righteous person. By actingwith intelligence the king may or may not succeed in acquiringwealth.[389] Aided by thy own intelligence do thou think what answershould be given to thy question on this head. Listen, O Bharata, to themeans, fraught with great merit, by which kings may conduct themselves(during seasons of distress). For the sake of true morality, however, Iwould not call those means righteous. If the treasury be filled byoppression, conduct like this brings the king to the verge ofdestruction. Even this is the conclusion of all intelligent men who havethought upon the subject. The kind of scriptures or science which onealways studies gives him the kind of knowledge which it is capable ofgiving. Such Knowledge verily becomes agreeable to him. Ignorance leadsto barrenness of invention in respect of means. Contrivance of means,again, through the aid of knowledge, becomes the source of greatfelicity. Without entertaining any scruples and any malice,[390] listento these instructions. Through the decrease of the treasury, the king’sforces are decreased. The king should, therefore, fill his treasury (byany means) like to one creating water in a wilderness which is withoutwater. Agreeably to this code of quasi-morality practised by theancients, the king should, when the time for it comes,[391] showcompassion to his people. This is eternal duty. For men that are able andcompetent,[392] the duties are of one kind. In seasons of distress,however, one’s duties are of a different kind. Without wealth a king may(by penances and the like) acquire religious merit. Life, however, ismuch more important than religious merit. (And as life cannot besupported without wealth, no such merit should be sought which stands inthe way of the acquisition of wealth). A king that is weak, by acquiringonly religious merit, never succeeds in obtaining just and proper meansfor sustenance; and since he cannot, by even his best exertions, acquirepower by the aid of only religious merit, therefore the practices inseasons of distress are sometimes regarded as not inconsistent withmorality. The learned, however, are of opinion that those practices leadto sinfulness. After the season of distress is over, what should theKshatriya do? He should (at such a time) conduct himself in such a waythat his merit may not be destroyed. He should also act in such a waythat he may not have to succumb to his enemies.[393] Even these have beendeclared to be his duties. He should not sink in despondency. He shouldnot (in times of distress) seek to rescue (from the peril of destruction)the merit of others or of himself. On the other hand, he should rescuehis own self. This is the settled conclusion.[394] There is this Sruti,viz., that it is settled that Brahmanas, who are conversant with duties,should have proficiency in respect of duties. Similarly, as regards theKshatriya, his proficiency should consist in exertion, since might ofarms is his great possession. When a Kshatriya’s means of support aregone, what should he not take excepting what belongs to ascetics and whatis owned by Brahmanas? Even as a Brahmana in a season of distress mayofficiate at the sacrifice of a person for whom he should never officiate(at other and ordinary times) and eat forbidden food, so there is nodoubt that a Kshatriya (in distress) may take wealth from every oneexcept ascetics and Brahmanas. For one afflicted (by an enemy and seekingthe means of escape) what can be an improper outlet? For a person immured(within a dungeon and seeking escape) what can be an improper path? Whena person becomes afflicted, he escapes by even an improper outlet. For aKshatriya that has, in consequence of the weakness of his treasury andarmy, become exceedingly humiliated, neither a life of mendicancy nor theprofession of a Vaisya or that of a Sudra has been laid down. Theprofession ordained for a Kshatriya is the acquisition of wealth bybattle and victory. He should never beg of a member of his own order. Theperson who supports himself at ordinary times by following the practicesprimarily laid for him, may in seasons of distress support himself byfollowing the practices laid down in the alternative. In a season ofdistress, when ordinary practices cannot be followed, a Kshatriya maylive by even unjust and improper means. The very Brahmanas, it is seen,do the same when their means of living are destroyed. When the Brahmanas(at such times) conduct themselves thus, what doubt is there in respectof Kshatriyas? This is, indeed, settled. Without sinking into despondencyand yielding to destruction, a Kshatriya may (by force) take what he canfrom persons that are rich. Know that the Kshatriya is the protector andthe destroyer of the people, Therefore, a Kshatriya in distress shouldtake (by force) what he can, with a view to (ultimately) protect thepeople. No person in this world, O king, can support life withoutinjuring other creatures. The very ascetic leading a solitary life in thedepths of the forest is no exception. A Kshatriya should not live,relying upon destiny,[395] especially he, O chief of the Kurus, who isdesirous of ruling. The king and the kingdom should always mutuallyprotect each other. This is an eternal duty. As the king protects, byspending all his possessions, the kingdom when it sinks into distress,even so should the kingdom protect the king when he sinks into distress.The king even at the extremity of distress, should never give up[396] histreasury, his machinery for chastising the wicked, his army, his friendsand allies and other necessary institutions and the chiefs existing inhis kingdom. Men conversant with duty say that one must keep one’s seeds,deducting them from one’s very food. This is a truth cited from thetreatise of Samvara well-known for his great powers of illusion, Fie onthe life of that king whose kingdom languishes. Fie on the life of thatman who from want of means goes to a foreign country for a living. Theking’s roots are his treasury and army. His army, again, has its roots inhis treasury. His army is the root of all his religious merits. Hisreligious merits, again are the root of his subjects. The treasury cannever be filled without oppressing others. How ‘then can the army be keptwithout oppression? The king, therefore, in seasons of distress, incursno fault by oppressing his subjects for filling the treasury. Forperforming sacrifices many improper acts are done. For this reason a kingincurs no fault by doing improper acts (when the object is to fill histreasury in a season of distress). For the sake of wealth practices otherthan those which are proper are followed (in seasons of distress). If (atsuch times) such improper practices be not adopted, evil is certain toresult. All those institutions that are kept up for working destructionand misery exist for the sake of collecting wealth.[397] Guided by suchconsiderations, all intelligent king should settle his course (at suchtimes). As animals and other things are necessary for sacrifices, assacrifices are for purifying the heart, and as animals, sacrifices, andpurity of the heart are all for final emancipation, even so policy andchastisement exist for the treasury, the treasury exists for the army,and policy and treasury and army all the three exist for vanquishing foesand protecting or enlarging the kingdom. I shall here cite an exampleillustrating the true ways of morality. A large tree is cut down formaking of it a sacrificial stake. In cutting it, other trees that standin its way have also to be cut down. These also, in falling down, killothers standing on the spot. Even so they that stand in the way of makinga well-filled treasury must have to be slain. I do not see how elsesuccess can be had. By wealth, both the worlds, viz., this and the other,can be had, as also Truth and religious merit. A person without wealth ismore dead than alive. Wealth for the performance of sacrifices should beacquired by every means. The demerit that attaches to an act done in aseason of distress is not equal to that which attaches to the same act ifdone at other times, O Bharata! The acquisition of wealth and itsabandonment cannot both be possibly seen in the same person, O king! I donot see a rich man in the forest. With respect to every wealth that isseen in this world, every one contends with every one else, saying, ‘Thisshall be mine,’ ‘This shall be mine!’ This is nothing, O scorcher offoes, that is so meritorious for a king as the possession of a kingdom.It is sinful for a king to oppress his subjects with heavy impositions atordinary times. In a season, however, of distress, it is quite different.Some acquire wealth by gifts and sacrifices; some who have a liking forpenances acquire wealth by penances; some acquire it by the aid of theirintelligence and cleverness. A person without wealth is said to be weak,while he that has wealth become powerful. A man of wealth may acquireeverything. A king that has well-filled treasury succeeds inaccomplishing everything. By his treasury a king may earn religiousmerit, gratify his desire for pleasure, obtain the next world, and thisalso. The treasury, however, should be filled by the aid of righteousnessand never by unrighteous practices, such, that is, as pass for righteousin times of distress.