Chapter 139

“Yudhishthira said, ‘Thou hast laid it down, O mighty one, that no trustshould be placed upon foes. But how would the king maintain himself if hewere not to trust anybody? From trust, O king, thou hast said, greatdanger arises to kings. But how, O monarch, can a king, without trustingothers, conquer his foes? Kindly remove this doubt of mine. My mind hasbecome confused, O grandsire, at what I have heard thee say on thesubject of mistrust.’

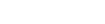

“Bhishma said, ‘Listen, O king, to what happened at the abode ofBrahmadatta, viz., the conversation between Pujani and king Brahmadatta.There was a bird named Pujani who lived for a long time with kingBrahmadatta in the inner apartments of his palace at Kampilya. Like thebird Jivajivaka, Pujani could mimic the cries of all animals. Though abird by birth, she had great knowledge and was conversant with everytruth. While living there, she brought forth an offspring of greatsplendour. At the very same time the king also got by his queen a son.Pujani, who was grateful for the shelter of the king’s roof, used everyday to go to the shores of the ocean and bring a couple of fruits for thenourishment of her own young one and the infant prince. One of thosefruits she gave to her own child and the other she gave to the prince.The fruits she brought were sweet as nectar, and capable of increasingstrength and energy. Every day she brought them and everyday she disposedof them in the same way. The infant prince derived great strength fromthe fruit of Pujani’s giving that he ate. One day the infant prince,while borne on the arms of his nurse, saw the little offspring of Pujani.Getting down from the nurse’s arms, the child ran towards the bird, andmoved by childish impulse, began to Play with it, relishing the sporthighly. At length, raising the bird which was of the same age withhimself in his hands, the prince pressed out its young life and then cameback to his nurse. The dam, O king, who had been out in her search afterthe accustomed fruits, returning to the palace, beheld her young onelying on the ground, killed by the prince. Beholding her son deprived oflife, Pujani, with tears gushing down her cheeks, and heart burning withgrief, wept bitterly and said, ‘Alas, nobody should live with a Kshatriyaor make friends with him or take delight in any intercourse with him.When they have any object to serve, they behave with courtesy. When thatobject has been served they cast off the instrument. The Kshatriyas doevil unto all. They should never be trusted. Even after doing an injurythey always seek to soothe and assure the injured for nothing. I shallcertainly take due vengeance, for this act of hostility, upon this crueland ungrateful betrayer of confidence. He has been guilty of a triple sinin taking the life of one that was horn on the same day with him and thatwas being reared with him in the same place, that used to eat with him,and that was dependent on him for protection.’ Having said these wordsunto herself, Pujani, with her talons, pierced the eyes of the prince,and deriving some comfort from that act of vengeance, once more said, ‘Asinful act, perpetrated deliberately, assails the doer without any lossof time. They. on the other hand, who avenge themselves of an injury,never lose their merit by such conduct. If the consequence of a sinfulact be not seen in the perpetrator himself, they would certainly be seen,O king, in his sons or son’s sons or daughter’s sons. Brahmadatta,beholding his son blinded by Pujani and regarding the act to have been aproper vengeance for what his son had done, said these words unto Pujani.’

“Brahmadatta said, ‘An injury was done by us to thee. Thou hast avengedit by doing an injury in return. The account has been squared. Do notleave thy present abode. On the other hand, continue to dwell here, OPujani.’

“Pujani said, ‘If a person having once injured another continues toreside with that other, they that are possessed of learning never applaudhis conduct. Under such circumstances it is always better for the injurerto leave his old place. One should never place one’s trust upon thesoothing assurances received from an injured party. The fool that trustssuch assurances soon meets with destruction. Animosity is not quicklycooled. The very sons and grandsons of persons that have injured eachother meet with destruction (in consequence of the quarrel descendinglike an inheritance). In consequence again of such destruction of theiroffspring, they lose the next world also. Amongst men that have injuredone another, mistrust would be productive of happiness. One that hasbetrayed confidence should never be trusted in the least. One who is notdeserving of trust should not be trusted; nor should too much trust beplaced upon a person deserving of trust. The danger that arises fromblind confidence brings about a destruction that is complete. One shouldseek to inspire others with confidence in one’s self. One, however,should never repose confidence on others. The father and the mother onlyare the foremost of friends. The wife is merely a vessel for drawing theseeds. The son is only one’s seed. The brother is a foe. The friend orcompanion requires to have his palms oiled if he is to remain so. One’sown self it is that enjoys or suffers one’s happiness or misery. Amongstpersons that have injured one another, it is not advisable there shouldbe (real) peace. The reasons no longer exists for which I lived here. Themind of a person who has once injured another becomes naturally filledwith mistrust, if he sees the injured person worshipping him with giftsand honours. Such conduct, especially when displayed by those that arestrong, always fills the weak with alarm. A person possessed ofintelligence should leave that place where he first meets with honour inorder to meet only with dishonour and injury next. In spite of anysubsequent honour that he might obtain from his enemy, he should behavein this way. I have dwelt in thy abode for a longtime, all along honouredby thee. A cause of enmity, however, has at last arisen. I should,therefore, leave this place without any hesitation.’

“Brahmadatta said, ‘One who does an injury in return for an injuryreceived is never regarded as offending. Indeed, the avenger squares hisaccount by such conduct. Therefore, O Pujani, continue to reside herewithout leaving this place.’

“Pujani said, ‘No friendship can once more be cemented between a personthat has injured and him that has inflicted an injury in return. Thehearts of neither can forget what has happened.’

“Brahmadatta said, ‘It is necessary that a union should take placebetween an injurer and the avenger of that injury. Mutual animosity, uponsuch a union, has been seen to cool. No fresh injury also has followed insuch cases.’

“Pujani said, ‘Animosity (springing from mutual injuries) can never die.The person injured should never trust his foes, thinking, ‘O, I have beensoothed with assurances of goodwill.’ In this world, men frequently meetwith destruction in consequence of (misplaced) confidence. For thisreason it is necessary that we should no longer meet each other. They whocannot be reduced to subjection by the application of even force andsharp weapons, can be conquered by (insincere) conciliation like (wild)elephants through a (tame) she-elephant.’

“Brahmadatta said, ‘From the fact of two persons residing together, evenif one inflicts upon the other deadly injury, an affection arisesnaturally between them, as also mutual trust as in the case, of theChandala and the dog. Amongst persons that have injured one another,co-residence blunts the keenness of animosity. Indeed, that animositydoes not last long, but disappears quickly like water poured upon theleaf of a lotus.’

“Pujani said, ‘Hostility springs from five causes. Persons possessed oflearning know it. Those five causes are woman, land, harsh words, naturalincompatibility, and injury.[414] When the person with whom hostilityoccurs happens to be a man of liberality, he should never be slain,particularly by a Kshatriya, openly or by covert means. In such a case,the man’s fault should be properly weighed.[415] When hostility hasarisen with even a friend, no further confidence should be reposed uponhim. Feelings of animosity lie hid like fire in wood. Like the Aurvyafire within the waters of the ocean, the fire of animosity can never beextinguished by gifts of wealth, by display of prowess, by conciliation,or by scriptural learning. The fire of animosity, once ignited, theresult of an injury once inflicted, is never extinguished, O king,without consuming out the right one of the parties. One, having injured aperson, should never trust him again as one’s friend, even though onemight have (after the infliction of the injury) worshipped him withwealth and honours. The fact of the injury inflicted fills the injurerwith fear. I never injured thee. Thou also didst never do me an injury.For this reason I dwelt in thy abode. All that is changed, and at presentI cannot trust thee.’

“Brahmadatta said, ‘It is Time that does every act, Acts are of diversekinds, and all of them proceed from Time. Who, therefore, injureswhom?[416] Birth and Death happen in the same way. Creatures act (i.e.,take birth and live) in consequence of Time, and it is in consequencealso of Time that they cease to live. Some are seen to die at once. Somedie one at a time. Some are seen to live for long periods. Like fireconsuming the fuel, Time consumes all creatures. O blessed lady, I am,therefore, not the cause of your sorrow, nor art thou the cause of mine.It is Time that always ordains the weal and woe of embodied creatures. Dothou then continue to dwell here according to thy pleasure, withaffection for me and without fear of any injury from me. What thou hastdone has been forgiven by me. Do thou also forgive me, O Pujani!’

“Pujani said, ‘If Time, according to thee, be the cause of all acts, thenof course nobody can cherish feelings of animosity towards anybody onearth. I ask, however, why friends and kinsmen, seek to avenge themselvesthe slain. Why also did the gods and the Asuras in days of your smiteeach other in battle? If it is Time that causes weal and woe and birthand death, why do physicians, then seek, to administer medicines to thesick? If it is Time that is moulding everything, what need is there ofmedicines? Why do people, deprived of their senses by grief, indulge insuch delirious rhapsodies? If Time, according to thee, be the cause ofacts, how can religious merit be acquired by persons performing religiousacts? Thy son killed my child. I have injured him for that. I have bythat act, O king, become liable to be slain by thee. Moved by grief formy son, I have done this injury to thy son. Listen now to the reason whyI have become liable to be killed by thee. Men wish for birds either tokill them for food or to keep them in cages for sport. There is no thirdreason besides such slaughter or immurement for which men would seekindividuals of our species. Birds, again, from fear of being eitherkilled or immured by men seek safety in Right. Persons conversant withthe Vedas have said that death and immurement are both painful. Life isdear unto all. All creatures are made miserable by grief and pain. Allcreatures wish for happiness. Misery arises from various sources.Decrepitude, O Brahmadatta, is misery. The loss of wealth is misery. Theadjacence of anything disagreeable or evil is misery. Separation ordissociation from friends and agreeable objects is misery. Misery arisesfrom death and immurement. Misery arises from causes connected with womenand from other natural causes. The misery that arises from the death ofchildren alters and afflicts all creatures very greatly. Some foolishpersons say that there is no misery in others’ misery.[417] Only he whohas not felt any misery himself can say so in the midst of men. He,however, that has felt sorrow and misery, would never venture to say so.One that has felt the pangs of every kind of misery feels the misery ofothers as one’s own. What I have done to thee, O king, and what thou hasdone to me, cannot be washed away by even a hundred years After what wehave done to each other, there cannot be a reconciliation. As often asthou wilt happen to think of thy son, thy animosity towards me willbecome fresh. If a person after avenging oneself of an injury, desires tomake peace with the injured, the parties cannot be properly reunited evenlike the fragments of an earthen vessel. Men conversant with scriptureshave laid it down that trust never produces happiness Usanas himself sangtwo verses unto Prahlada in days of old. He who trusts the words, true orfalse, of a foe, meets with destruction like a seeker of honey, in a pitcovered with dry grass.[418] Animosities are seen to survive the verydeath of enemies, for persons would speak of the previous quarrels oftheir deceased sires before their surviving children. Kings extinguishanimosities by having recourse to conciliation but, when the opportunitycomes, break their foes into pieces like earthen jars full of waterdashed upon stone. If the king does injury to any one, he should nevertrust him again. By trusting a person who has been injured, one has tosuffer great misery.

“Brahmadatta said, ‘No man can obtain the fruition of any object bywithholding his trust (from others). By cherishing fear one is alwaysobliged to live as a dead person.’

“Pujani said, ‘He whose feet have become sore, certainly meets with afall if he seeks to move, move he may howsoever cautiously. A man who hasgot sore eyes, by opening them against the wind, finds them exceedinglypained by the wind. He who, without knowing his own strength, sets footon a wicked path and persists in walking along it, soon loses his verylife as the consequence. The man who, destitute of exertion, tills hisland, disregarding the season of rain, never succeeds in obtaining aharvest. He who takes every day food that is nutritive, be it bitter orastringent or palatable or sweet, enjoys a long life. He, on the otherhand, who disregards wholesome food and takes that which is injuriouswithout an eye to consequences, soon meets with death. Destiny andExertion exist, depending upon each other. They that are of high soulsachieve good and great feats, while eunuchs only pay court to Destiny. Beit harsh or mild, an act that is beneficial should be done. Theunfortunate man of inaction, however, is always overwhelmed by all sortsof calamity. Therefore, abandoning everything else, one should put forthhis energy. Indeed, disregarding everything, men should do what isproductive of good to themselves. Knowledge, courage, cleverness,strength, and patience are said to be one’s natural friends. They thatare possessed of wisdom pass their lives in this world with the aid ofthese five. Houses, precious metals, land, wife, and friends,–these aresaid by the learned to be secondary sources of good. A man may obtainthem everywhere. A person possessed of wisdom may be delightedeverywhere. Such a man shines everywhere. He never inspires anybody withfear. If sought to be frightened, he never yields to fear himself. Thewealth, however little, that is possessed at any time by an intelligentman is certain to increase. Such a man does every act with cleverness. Inconsequence of self-restraint, he succeeds in winning great fame.Home-keeping men of little understanding have to put up with termagantwives that eat up their flesh like the progeny of a crab eating up theirdam. There are men who through loss of understanding become verycheerless at the prospect of leaving home. They say untothemselves,–These are our friends! This is our country! Alas, how shallwe leave these?–One should certainly leave the country of one’s birth,if it be afflicted by plague or famine. One should live in one’s owncountry, respected by all, or repair to a foreign country for livingthere. I shall, for this reason, repair to some other region. I do notventure to live any longer in this place, for I have done a great wrongto thy child, O king, one should from a distance abandon a bad wife, abad son, a bad king, a bad friend, a bad alliance, and a bad country. Oneshould not place any trust on a bad son. What joy can one have in a badwife? There cannot be any happiness in a bad kingdom. In a bad countryone cannot hope to obtain a livelihood. There can be no lastingcompanionship with a bad friend whose attachment is very uncertain. In abad alliance, when there is no necessity for it, there is disgrace. Sheindeed, is a wife who speaks only what is agreeable. He is a son whomakes the sire happy. He is a friend in whom one can trust. That indeed,is one’s country where one earns one’s living. He is a king of strictrule who does not oppress, who cherishes the poor and in whoseterritories there is no fear. Wife, country, friends, son, kinsmen, andrelatives, all these one can have if the king happens to be possessed ofaccomplishments and virtuous eyes. If the king happens to be sinful, hissubjects, inconsequence of his oppressions, meet with destruction. Theking is the root of one’s triple aggregate (i.e., Virtue, Wealth, andPleasure). He should protect his subjects with heedfulness. Taking fromhis subjects a sixth share of their wealth, he should protect them all.That king who does not protect his subjects is truly a thief. That kingwho, after giving assurances of protection, does not, from rapacity,fulfil them,–that ruler of sinful soul,–takes upon himself the sins ofall hi subjects and ultimately sinks into hell. That king, on the otherhand, who, having given assurances of protection, fulfils them, comes tobe regarded as a universal benefactor in consequence of protecting allhis subjects. The lord of all creatures, viz., Manu, has said that theking has seven attributes: he is mother, father, preceptor, protector,fire, Vaisravana and Yama. The king by behaving with compassion towardshis people is called their father. The subject that behaves falselytowards him takes birth in his next life as an animal or a bird. By doinggood to them and by cherishing the poor, the king becomes a mother untohis people. By scorching the wicked he comes to be regarded as fire, andby restraining the sinful he comes to be called Yama. By making gifts ofwealth unto those that are dear to him, the king comes to be regarded asKuvera, the grantor of wishes. By giving instruction in morality andvirtue, he becomes a preceptor, and by exercising the duty of protectionhe becomes the protector. That king who delights the people of his citiesand provinces by means of his accomplishments, is never divested of hiskingdom in consequence of such observance of duty. That king who knowshow to honour his subjects never suffers misery either here or hereafter.That king whose subjects are always filled with anxiety or overburdenedwith taxes, and overwhelmed by evils of every kind, meets with defeat atthe hands of his enemies. That king, on the other hand, whose subjectsgrow like a large lotus in a lake succeeds in obtaining every reward hereand at last meets with honour in heaven. Hostility with a person that ispowerful is, O king, never applauded. That king who has incurred thehostility of one more powerful than himself, loses both kingdom andhappiness.’

“Bhishma continued, ‘The bird, having said these words, O monarch, untoking Brahmadatta, took the king’s leave and proceeded to the region shechose. I have thus recited to thee, O foremost of kings, the discoursebetween Brahmadatta and Pujani. What else dost thou wish to hear?’