Chapter 321

“Yudhishthira said, ‘Without abandoning the domestic mode of life, Oroyal sage of Kuru’s race, who ever attained to Emancipation which is theannihilation of the Understanding (and the other faculties)? Do tell methis! How may the gross and the subtile form be cast off? Do thou also, Ograndsire, tell me what the supreme excellence of Emancipation is.’

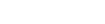

“Bhishma said, ‘In this connection is cited the old narrative of thediscourse between Janaka and Sulabha, O Bharata! In days of yore therewas a king of Mithila, of the name of Dharmadhyaja, of Janaka’s race. Hewas devoted to the practices of the religion of Renunciation. He was wellconversant with the Vedas, with the scriptures on Emancipation, and withthe scriptures bearing on his own duty as a king. Subjugating his senses,he ruled his Earth. Hearing of his good behaviour in the world, many menof wisdom, well-conversant with wisdom, O foremost of men, desired toimitate him. ‘In the same Satya Yuga, a woman of the name of Sulabha,belonging to the mendicant order, practised the duties of Yoga andwandered over the whole Earth. In course of her wanderings over theEarth, Sulabha heard from many Dandis of different places that the rulerof Mithila was devoted to the religion of Emancipation. Hearing thisreport about king Janaka and desirous of ascertaining whether it was trueor not, Sulabha became desirous of having a personal interview withJanaka. Abandoning, by her Yoga powers, her former form and features,Sulabha assumed the most faultless features and unrivalled beauty. In thetwinkling of an eye and with the speed of the quickest shaft, thefair-browed lady of eyes like lotus-petals repaired to the capital of theVidehas. Arrived at the chief city of Mithila teeming with a largepopulation, she adopted the guise of a mendicant and presented herselfbefore the king. The monarch, beholding, her delicate form, became filledwith wonder and enquired who she was, whose she was, and whence she came.Welcoming her, he assigned her an excellent seat, honoured her byoffering water to wash her feet, and gratified her with excellentrefreshments. Refreshed duly and gratified with the rites of hospitalityoffered unto her, Sulabha, the female mendicant, urged the king, who wassurrounded by his ministers and seated in the midst of learned scholars,(to declare himself in respect of his adherence to the religion ofEmancipation). Doubting whether Janaka had succeeded in attaining toEmancipation, by following the religion of Nivritti, Sulabha, endued withYoga-power, entered the understanding of the king by her ownunderstanding. Restraining, by means of the rays of light that emanatedfrom her own eyes, the rays issuing from the eyes of the king, the lady,desirous of ascertaining the truth, bound up king Janaka with Yogabonds.[1677]’ That best of monarch, priding himself upon his owninvincibleness and defeating the intentions of Sulabha seized herresolution with his own resolution.[1678] The king, in his subtile form,was without the royal umbrella and sceptre. The lady Sulabha, in hers,was without the triple stick. Both staying then in the same (gross) form,thus conversed with each other. Listen to that conversation as ithappened between the monarch and Sulabha.

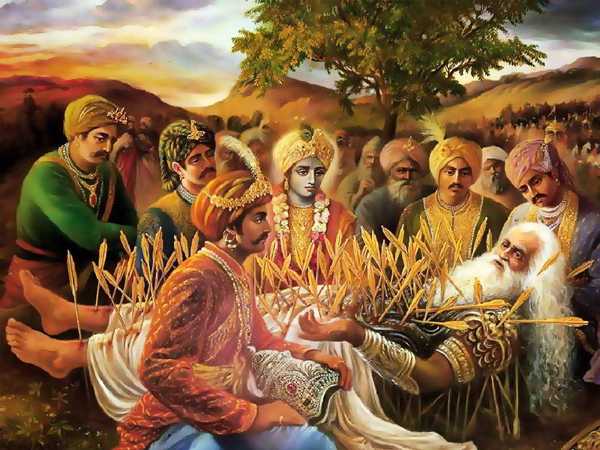

“Janaka said, O holy lady, to what course of conduct art thou devoted?Whose art thou? Whence hast thou come? After finishing thy business here,whither wilt thou go? No one can, without questioning, ascertainanother’s acquaintance with the scriptures, or age, or order of birth.Thou shouldst, therefore, answer these questions of mine, when thou hascome to me. Know that I am truly freed from all vanity in respect of myroyal umbrella and sceptre. I wish to know thee thoroughly. Thou artdeserving I hold, of my respect.[1679] Do thou listen to me as I speak tothee on Emancipation for there is none else (in this world) that candiscourse to thee on that topic. Hear me also I tell thee who that personis from whom in days of old I acquired this distinguishingknowledge.[1680] I am the beloved disciple of the high-souled andvenerable Panchasikha, belonging to the mendicant order, of Parasara’srace. My doubts have been dispelled and am fully conversant with theSankhya and the Yoga systems, and the ordinances as in respect ofsacrifices and other rites, which constitutes the three well-known pathsof Emancipation.[1681] Wandering over the earth and pursuing the whilethe path that is pointed out by the scriptures, the learned Panchasikhaformerly dwelt in happiness in my abode for a period of four months inthe rainy season. That foremost of Sankhyas discoursed to me, agreeablyto the truth, and in an intelligible manner suited to my comprehension,on the several kinds of means for attaining to Emancipation. He did not,however, command me to give up my kingdom. Freed from attachments, andfixing my Soul on supreme Brahma, and unmoved by companionship, I lived,practising in its entirety that triple conduct which is laid down intreatises on Emancipation. Renunciation (of all kinds of attachments) isthe highest means prescribed for Emancipation. It is from Knowledge thatRenunciation, by which one becomes freed is said to flow. From Knowledgearises the endeavour after Yoga, and through that endeavour one attainsto knowledge of Self or Soul. Through knowledge of Self one transcendsjoy and grief. That enables one to transcend death and attain to highsuccess. That high intelligence (knowledge of Self) has been acquired byme, and accordingly I have transcended all pairs of opposites. Even inthis life have I been freed from stupefaction and have transcended allattachments. As a soil, saturated with water and softened thereby, causesthe (sown) seed to sprout forth, after the same manner, the acts of mencause rebirth. As a seed, fried on a pan or otherwise, becomes unable tosprout forth although the capacity for sprouting was there, after thesame manner my understanding having been freed from the productiveprinciple constituted by desire, by the instruction of the holyPanchasikha of the mendicant order, it no longer produces its fruit inthe form of attachment to the object of the senses. I never experiencelove for my spouse or hate for my foes. Indeed, I keep aloof from both,beholding the fruitlessness of attachment and wrath. I regard bothpersons equally, viz., him that smears my right hand with sandal-pasteand him that wounds my left. Having attained my (true) object, I amhappy, and look equally upon a clod of earth, a piece of stone, and alump of gold. I am freed from attachments of every kind, though amengaged in ruling a kingdom. In consequence of all this I amdistinguished over all bearers of triple sticks. Some foremost of menthat are conversant with the topic of Emancipation say that Emancipationhas a triple path, (these are knowledge, Yoga, and sacrifices and rites).Some regard knowledge having all things of the world for its object asthe means of emancipation. Some hold that the total renunciation of acts(both external and internal) is the means thereof. Another class ofpersons conversant with the scriptures of Emancipation say that Knowledgeis the single means. Other, viz. Yatis, endued with subtile vision, holdthat acts constitute the means. The high-souled Panchasikha, discardingboth the opinion about knowledge and acts, regarded the third as the onlymeans of Emancipation. If men leading the domestic mode of life be enduedwith Yama and Niyama, they become the equals of Sannyasins. If, on theother hand, Sannyasins be endued with desire and aversion and spouses andhonour and pride and affection, they become the equals of men leadingdomestic modes of life.[1682] If one can attain to Emancipation by meansof knowledge, then may Emancipation exist in triple sticks (for there isnothing to prevent the bearers of such stick from acquiring the needfulknowledge). Why then may Emancipation not exist in the umbrella and thesceptre as well, especially when there is equal reason in taking up thetriple stick and the sceptre?[1683] One becomes attached to all thosethings and acts with which one has need for the sake of one’s own selffor particular reasons.[1684] If a person, beholding the faults of thedomestic mode of life, casts it off for adopting another mode (which heconsiders to be fraught with great merit), be cannot, for such rejectionand adoption be regarded as one that is once freed from all attachments,(for all that he has done has been to attach himself to a new mode afterhaving freed himself from a previous one).[1685] Sovereignty is fraughtwith the rewarding and the chastising of others. The life of a mendicantis equally fraught with the same (for mendicants also reward and chastisethose they can). When, therefore, mendicants are similar to kings in thisrespect, why would mendicants only attain to Emancipation, and not kings?Notwithstanding the possession of sovereignty, therefore, one becomescleansed of all sins by means of knowledge alone, living the while inSupreme Brahma. The wearing of brown cloths, shaving of the head, bearingof the triple stick, and the Kamandalu,–these are the outward signs ofone’s mode of life. These have no value in aiding one to the attainmentof Emancipation. When, notwithstanding the adoption of these emblems of aparticular mode of life, knowledge alone becomes the cause of one’sEmancipation from sorrow, it would appear that the adoption of mereemblems is perfectly useless. Or, if, beholding the mitigation of sorrowin it, thou hast betaken thyself to these emblems of Sannyasi, why thenshould not the mitigation of sorrow be beheld in the umbrella and thesceptre to which I have betaken myself? Emancipation does not exist inpoverty; nor is bondage to be found in affluence. One attains toEmancipation through Knowledge alone, whether one is indigent oraffluent. For these reasons, know that I am living in a condition offreedom, though ostensibly engaged in the enjoyments of religion, wealth,and pleasure, in the form of kingdom and spouses, which constitute afield of bondage (for the generality of men). The bonds constituted bykingdom and affluence, and the bondage to attachments, I have cut offwith the sword of Renunciation whetted on the stone of the scripturesbearing upon Emancipation. As regards myself then, I tell thee that Ihave become freed in this way. O lady of the mendicant order, I cherishan affection for thee. But that should not prevent me from telling theethat thy behaviour does not correspond with the practices of the mode oflife to which thou hast betaken thyself! Thou hast great delicacy offormation. Thou hast an exceedingly shapely form. The age is young. Thouhast all these, and thou hast Niyama (subjugation of the senses). I doubtit verily. Thou hast stopped up my body (by entering into me with the aidof the Yoga power) for ascertaining as to whether I am really emancipatedor not. This act of thine ill corresponds with that mode of life whoseemblems thou bearest. For Yogin that is endued with desire, the triplestick is unfit. As regards thyself, thou dost not adhere to thy stick. Asregards those that are freed, it behoves even them to protect themselvesfrom fall.[1686] Listen now to me as to what thy transgression has beenin consequence of thy contact with me and thy having entered into mygross body with the aid of thy understanding. To what reason is thyentrance to be ascribed into my kingdom or my palace? At whose sign hastthou entered into my heart?[1687] Thou belongest to the foremost of allthe orders, being, as thou art, a Brahmana woman. As regards myself,however, I am a Kshatriya. There is no union for us two. Do not help tocause an intermixture of colours. Thou livest in the practice of thoseduties that lead to Emancipation. I live in the domestic mode of life,This act of thine, therefore, is another evil thou hast done, for itproduces an unnatural union of two opposite modes of life. I do not knowwhether thou belongest to my own gotra or dost not belong to it. Asregards thyself also, thou dost not know who I am (viz., to what gotra Ibelong). If thou art of my own gotra, thou hast, by entering into myperson, produced another evil,–the evil, viz., of unnatural union. If,again, thy husband be alive and dwelling in a distant place, thy unionwith me has produced the fourth evil of sinfulness, for thou art not onewith whom I may be lawfully united. Dost thou perpetrate all these sinfulacts, impelled by the motive of accomplishing a particular object? Dostthou do these from ignorance or from perverted intelligence? If, again,in consequence of thy evil nature thou hast thus become thoroughlyindependent or unrestrained in thy behaviour, I tell thee that if thouhast any knowledge of the scriptures, thou wilt understand thateverything thou hast done has been productive of evil. A third faultattaches to thee in consequence of these acts of thine, a fault that isdestructive of peace of mind. By endeavouring to display thy superiority,the indication of a wicked woman is seen in thee. Desirous of assertingthy victory as thou art, it is not myself alone whom thou wishest todefeat, for it is plain that thou wishest to obtain a victory over eventhe whole of my court (consisting of these learned and very superiorBrahmanas), by casting thy eyes in this way towards all these meritoriousBrahmanas, it is evident that thou desirest to humiliate them all andglorify thyself (at their expense). Stupefied by thy pride ofYoga-puissance that has been born of thy jealousy (at sight of my power,)thou hast caused a union of thy understanding with mine and thereby hastreally mingled together nectar with poison. That union, again, of man andwoman, when each covets the other, is sweet as nectar. That association,however, of man and woman when the latter, herself coveting, fails toobtain an individual of the opposite sex that does not covet her, is,instead of being a merit, only a fault that is as noxious as poison. Donot continue to touch me. Know that I am righteous. Do thou act accordingto thy own scriptures. The enquiry thou hadst wished to make, viz.,whether I am or I am not emancipated, has been finished. It behoves theenot to conceal from me all thy secret motives. It behoves thee not, thatthus disguisest thyself, to conceal from me what thy object is, that iswhether this call of thine has been prompted by the desire ofaccomplishing some object of thy own or whether thou hast come foraccomplishing the object of some other king (that is hostile to me). Oneshould never appear deceitfully before a king; nor before a Brahmana; norbefore one’s wife when that wife is possessed of every wifely virtue.Those who appear in deceitful guise before these three very soon meetwith destruction. The power of kings consists in their sovereignty. Thepower of Brahmanas conversant with the Vedas is in the Vedas. Women wielda high power in consequence of their beauty and youth and blessedness.These then are powerful in the possession of these powers. He, therefore,that is desirous of accomplishing his own object should always approachthese three with sincerity and candour, insincerity and deceit fail toproduce success (in these three quarters). It behoveth thee, therefore,to apprise me of the order to which thou belongest by birth, of thylearning and conduct and disposition and nature, as also of the objectthou hast in view in coming to this place!–”

“Bhishma continued, ‘Though rebuked by the king in these unpleasant,improper, and ill-applied words, the lady Sulabha was not at all abashed.After the king had said these words, the beautiful Sulabha then addressedherself for saying the following words in reply that were more handsomethan her person.

“‘Sulabha said, O king, speech ought always to be free from the nineverbal faults and the nine faults of judgment. It should also, whilesetting forth the meaning with perspicuity, be possessed of the eighteenwell-known merits.[1688] Ambiguity, ascertainment of the faults andmerits of premises and conclusions, weighing the relative strength orweakness of those faults and merits, establishment of the conclusion, andthe element of persuasiveness or otherwise that attaches to theconclusion thus arrived at,–these five characteristics appertaining tothe sense–constitute the authoritativeness of what is said. Listen nowto the characteristics of these requirements beginning with ambiguity,one after another, as I expound them according to the combinations. Whenknowledge rests on distinction in consequence of the object to be knownbeing different from one another, and when (as regards the comprehensionof the subject) the understanding rests upon many points one afteranother, the combination of words (in whose case this occurs) is said tobe vitiated by ambiguity.[1689] By ascertainment (of faults and merits),called Sankhya, is meant the establishment, by elimination, of faults ormerits (in premises and conclusions), adopting tentative meanings.[1690]Krama or weighing the relative strength or weakness of the faults ormerits (ascertained by the above process), consists in settling thepropriety of the priority or subsequence of the words employed in asentence. This is the meaning attached to the word Krama by personsconversant with the interpretation of sentences or texts. By Conclusionis meant the final determination, after this examination of what has beensaid on the subjects of religion, pleasure, wealth, and Emancipation, inrespect of what is particularly is that has been said in the text.[1691]The sorrow born of wish or aversion increases to a great measure. Theconduct, O king, that one pursues in such a matter (for dispelling thesorrow experienced) is called Prayojanam.[1692] Take it for certain, Oking, at my word, that these characteristics of Ambiguity and the other(numbering five in all), when occurring together, constitute a completeand intelligible sentence.[1693] The words I shall utter will be fraughtwith sense, free from ambiguity (in consequence of each of them not beingsymbols of many things), logical, free from pleonasm or tautology,smooth, certain, free from bombast, agreeable or sweet, truthful, notinconsistent with the aggregate of three, (viz., Righteousness, Wealthand Pleasure), refined (i.e., free from Prakriti), not elliptical orimperfect, destitute of harshness or difficulty of comprehension,characterised by due order, not far-fetched in respect of sense,corrected with one another as cause and effect and each having a specificobject.[1694] I shall not tell thee anything, prompted by desire or wrathor fear or cupidity or abjectness or deceit or shame or compassion orpride. (I answer thee because it is proper for me to answer what thouhast said). When the speaker, the hearer, and the words said, thoroughlyagree with one another in course of a speech, then does the sense ormeaning come out very clearly. When, in the matter of what is to be said,the speaker shows disregard for the understanding of the hearer byuttering words whose meaning is understood by himself, then, however goodthose words may be, they become incapable of being seized by thehearer.[1695] That speaker, again, who, abandoning all regard for his ownmeaning uses words that are of excellent sound and sense, awakens onlyerroneous, impressions in the mind of the hearer. Such words in suchconnection become certainly faulty. That speaker, however, who employswords that are, while expressing his own meaning, intelligible to thehearer, as well, truly deserves to be called a speaker. No other mandeserves the name. It behoveth thee, therefore, O king, to hear withconcentrated attention these words of mine, fraught with meaning andendued with wealth of vocables. Thou hast asked me who I am, whose I am,whence I am coming, etc. Listen to me, O king, with undivided mind, as Ianswer these questions of thine. As lac and wood, as grains of dust anddrops of water, exist commingled when brought together, even so are theexistences of all creatures.[1696] Sound, touch, taste, form, and scent,these and the senses, though diverse in respect of their essences, existyet in a state of commingling like lac and wood. It is again well knownthat nobody asks any of these, saying, who art thou? Each of them alsohas no knowledge either of itself or of the others. The eye cannot seeitself. The ear cannot hear itself. The eye, again, cannot discharge thefunctions of any of the other senses, nor can any of the senses dischargethe functions of any sense save its own. If all of them even combinetogether, even they fail to know their own selves as dust and watermingled together cannot know each other though existing in a state ofunion. In order to discharge their respective functions, they await thecontact of objects that are external to them. The eye, form, and light,constitute the three requisites of the operation called seeing. The same,as in this case, happens in respect of the operations of the other sensesand the ideas which is their result. Then, again, between the functionsof the senses (called vision, hearing, etc.,) and the ideas which aretheir result (viz., form, sound, etc.), the mind is an entity other thanthe senses And is regarded to have an action of its own. With its helpone distinguishes what is existent from what is non-existent for arrivingat certainty (in the matter of all ideas derived from the senses). Withthe five senses of knowledge and five senses of action, the mind makes atotal of eleven. The twelfth is the Understanding. When doubt arises inrespect of what is to be known, the Understanding comes forward andsettles all doubts (for aiding correct apprehension). After the twelfth,Sattwa is another principle numbering the thirteenth. With its helpcreatures are distinguished as possessing more of it or less of it intheir constitutions.[1697] After this, Consciousness (of self) is anotherprinciple (numbering the fourteenth). It helps one to an apprehension ofself as distinguished from what is not self. Desire is the fifteenthprinciple, O king. Unto it inhere the whole universe.[1698] The sixteenthprinciple is Avidya. Unto it inhere the seventeenth and the eighteenthprinciples called Prakriti and Vyakti (i.e., Maya and Prakasa). Happinessand sorrow, decrepitude and death, acquisition and loss, the agreeableend the disagreeable,–these constitute the nineteenth principle and arecalled couples of opposites. Beyond the nineteenth principle is another,viz., Time called the twentieth. Know that the births and death of allcreatures are due to the action of this twentieth principle. These twentyexist together. Besides these, the five Great primal elements, andexistence and non-existence, bring up the tale to seven and twenty.Beyond these, are three others, named Vidhi, Sukra, and Vala, that makethe tale reach thirty.[1699] That in which these ten and twentyprinciples occur is said to be body. Some persons regard unmanifestPrakriti to be the source or cause of these thirty principles. (This isthe view of the atheistic Sankhya school). The Kanadas of gross visionregard the Manifest (or atoms) to be their cause. Whether the Unmanifestor the Manifest be their cause, or whether the two (viz., the Supreme orPurusha and the Manifest or atoms) be regarded as their cause, orfourthly, whether the four together (viz., the Supreme or Purusha and hisMaya and Jiva and Avidya or Ignorance) be the cause, they that areconversant with Adhyatma behold Prakriti as the cause of all creatures.That Prakriti which is Unmanifest, becomes manifest in the form of theseprinciples. Myself, thyself, O monarch, and all others that are enduedwith body are the result of that Prakriti (so far as our bodies areconcerned). Insemination and other (embryonic) conditions are due to themixture of the vital seed and blood. In consequence of insemination theresult which first appears is called by the name of ‘Kalala.’ From’Kalala’ arises what is called Vudvuda (bubble). From the stage called’Vudvuda’ springs what is called ‘Pesi.’ From the condition called ‘Pesi’that stage arises in which the various limbs become manifested. From thislast condition appear nails and hair. Upon the expiration of the ninthmonth, O king of Mithila, the creature takes its birth so that, its sexbeing known, it comes to be called a boy or girl. When the creatureissues out of the womb, the form it presents is such that its nails andfingers seem to be of the hue of burnished copper. The next stage is saidto be infancy, when the form that was seen at the time of birth becomeschanged. From infancy youth is reached, and from youth, old age. As thecreature advances from one stage into another, the form presented in theprevious stage becomes changed. The constituent elements of the body,which serve diverse functions in the general economy, undergo changeevery moment in every creature. Those changes, however, are so minutethat they cannot be noticed.[1700] The birth of particles, and theirdeath, in each successive condition, can not be marked, O king, even asone cannot mark the changes in the flame of a burning lamp.[1701] Whensuch is the state of the bodies of all creatures,–that is when thatwhich is called the body is changing incessantly even like the rapidlocomotion of a steed of good mettle,–who then has come whence or notwhence, or whose is it or whose is it not, or whence does it not arise?What connection does there exist between creatures and their ownbodies?[1702] As from the contact of flint with iron, or from two sticksof wood when rubbed against each other, fire is generated, even so arecreatures generated from the combination of the (thirty) principlesalready named. Indeed, as thou thyself seest thy own body in thy body andas thou thyself seest thy soul in thy own soul, why is it that thou dostnot see thy own body and thy own soul in the bodies and souls of others?If it is true that thou seest an identity with thyself and others, whythen didst thou ask me who I am and whose? If it is true that hast, Oking been freed from the knowledge of duality that (erroneously)says–this is mine and this other is not mine,–then what use is therewith such questions as Who art thou, whose art thou and whence dost thoucome? What indications of Emancipation can be said to occur in that kingwho acts as others act towards enemies and allies and neutrals and invictory and truce and war? What indications of Emancipation occur in himwho does not know the true nature of the aggregate of three as manifestedin seven ways in all acts and who, on that account, is attached to thataggregate of three?[1703] What indications of Emancipation exist in himwho fails to cast an equal eye on the agreeable, on the weak, and thestrong? Unworthy as thou art of it, thy pretence of Emancipation shouldbe put down by thy counsellers! This thy endeavour to attain toEmancipation (when thou hast so many faults) is like the use of medicineby a patient who indulges in all kinds of forbidden food and practices. Ochastiser of foes, reflecting upon spouses and other sources ofattachment, one should behold these in one’s own soul. What else can belooked upon as the indication of Emancipation? Listen now to me as Ispeak in detail of these and certain other minute sources of attachmentappertaining to the four well known acts (of lying down for slumber,enjoyment, eating, and dressing) to which thou art still bound thoughthou professest thyself to have adopted the religion of Emancipation.That man who has to rule the whole world must, indeed, be a single kingwithout a second. He is obliged to live in only a single palace. In thatpalace he has again only one sleeping chamber. In that chamber he has,again, only one bed on which at night he is to lie down. Half that bedagain he is obliged to give to his Queen-consort. This may serve as anexample of how little the king’s share is of all he is said to own. Thisis the case with his objects of enjoyment, with the food he eats, andwith the robes he wears. He is thus attached to a very limited share ofall things. He is, again, attached to the duties of rewarding andpunishing. The king is always dependent on others. He enjoys a very smallshare of all he is supposed to own, and to that small share he is forcedto be attached (as well as others are attached to their respectivepossessions). In the matter also of peace and war, the king cannot besaid to be independent. In the matter of women, of sports and other kindsof enjoyment, the king’s inclinations are exceedingly circumscribed. Inthe matter of taking counsel and in the assembly of his councillors whatindependence can the king be said to have? When, indeed, he sets hisorders on other men, he is said to be thoroughly independent. But thenthe moment after, in the several matters of his orders, his independenceis barred by the very men whom he has ordered.[1704] If the king desiresto sleep, he cannot gratify his desire, resisted by those who havebusiness to transact with him. He must sleep when permitted, and whilesleeping he is obliged to wake up for attending to those that have urgentbusiness with him–bathe, touch, drink, eat, pour libations on the fire,perform sacrifices, speak, hear,–these are the words which kings have tohear from others and hearing them have to slave to those that utter them.Men come in batches to the king and solicit him for gifts. Being,how-ever, the protector of the general treasury, he cannot make giftsunto even the most deserving. If he makes gifts, the treasury becomesexhausted. If he does not, disappointed solicitors look upon him withhostile eyes. He becomes vexed and as the result of this, misanthropicalfeelings soon invade his mind. If many wise and heroic and wealthy menreside together, the king’s mind begins to be filled with distrust inconsequence. Even when there is no cause of fear, the king entertainsfear of those that always wait upon and worship him. Those I havementioned O king, also find fault with him. Behold, in what way theking’s fears may arise from even them! Then again all men are kings intheir own houses. All men, again, in their own houses are house-holders.Like kings, O Janaka, all men in their own houses chastise and reward.Like kings others also have sons and spouses and their own selves andtreasuries and friends and stores. In these respects the king is notdifferent from other men.–The country is ruined,–the city is consumedby fire,–the foremost of elephants is dead,–at all this the king yieldsto grief like others, little regarding that these impressions are all dueto ignorance and error. The king is seldom freed from mental griefscaused by desire and aversion and fear. He is generally afflicted also byheadaches and diverse diseases of the kind. The king is afflicted (likeothers) by all couples of opposites (as pleasure and pain, etc). He isalarmed at everything. Indeed, full of foes and impediments as kingdomis, the king, while he enjoys it, passes nights of sleeplessness.Sovereignty, therefore, is blessed with an exceedingly small share ofhappiness. The misery with which it is endued is very great. It is asunsubstantial as burning flames fed by straw or the bubbles of froth seenon the surface of water. Who is there that would like to obtainsovereignty, or having acquired sovereignty can hope to win tranquillity?Thou regardest this kingdom and this palace to be thine. Thou thinkestalso this army, this treasury, and these counsellers to belong to thee.Whose, however, in reality are they, and whose are they not? Allies,ministers, capital, provinces, punishment, treasury, and the king, theseseven which constitute the limbs of a kingdom exist, depending upon oneanother, like three sticks standing with one another’s support. Themerits of each are set off by the merits of the others. Which of them canbe said to be superior to the rest? At those times those particular onesare regarded as distinguished above the rest when some important end isserved through their agency. Superiority, for the time being, is said toattach to that one whose efficacy is thus seen. The seven limbs alreadymentioned, O best of kings, and the three others, forming an aggregate often, supporting one another, are said to enjoy the kingdom like the kinghimself.[1705] That king who is endued with great energy and who isfirmly attached to Kshatriya practices, should be satisfied with only atenth part of the produce of the subject’s field. Other kings are seen tobe satisfied with less than a tenth part of such produce. There is no onewho owns the kingly office without some one else owning it in the world,and there is no kingdom without a king.[1706] If there be no kingdom,there can be no righteousness, and if there be no righteousness, whencecan Emancipation arise? Whatever merit is most sacred and the highest,belongs to kings and kingdoms.[1707] By ruling a kingdom well, a kingearns the merit that attaches to a Horse-sacrifice with the whole Earthgiven away as Dakshina. But how many kings are there that rule theirkingdoms well? O ruler of Mithila, I can mention hundreds and thousandsof faults like these that attach to kings and kingdoms. Then, again, whenI have no real connection with even my body, how then can I be said tohave any contact with the bodies of others? Thou canst not charge me withhaving endeavoured to bring about an intermixture of castes. Hast thouheard the religion of Emancipation in its entirety from the lips ofPanchasikha together with its means, its methods, its practices, and itsconclusion?[1708] If thou hast prevailed over all thy bonds and freedthyself from all attachments, may I ask thee, O king, who thou preservestthy connections still with this umbrella and these other appendages ofroyalty? I think that thou hast not listened to the scriptures, or, thouhast listened to them without any advantage, or, perhaps, thou hastlistened to some other treatises looking like the scriptures. It seemsthat thou art possessed only of worldly knowledge, and that like anordinary man of the world thou art bound by the bonds of touch andspouses and mansions and the like. If it be true that thou Met beenemancipated from all bonds, what harm have I done thee by entering thyperson with only my Intellect? With Yatis, among all orders of men, thecustom is to dwell in uninhabited or deserted abodes. What harm then haveI done to whom by entering thy understanding which is truly of realknowledge? I have not touched thee, O king, with my hands, of arms, orfeet, or thighs, O sinless one, or with any other part of the body. Thouart born in a high race. Thou hast modesty. Thou hast foresight. Whetherthe act has been good or bad, my entrance into thy body has been aprivate one, concerning us two only. Was it not improper for thee topublish that private act before all thy court? These Brahmanas are allworthy of respect. They are foremost of preceptors. Thou also artentitled to their respect, being their king. Doing them reverence, thouart entitled to receive reverence from them. Reflecting on all this, itwas not proper for thee to proclaim before these foremost of men the factof this congress between two persons of opposite sexes, if, indeed, thouart really acquainted with the rules of propriety in respect of speech. Oking of Mithila, I am staying in thee without touching thee at all evenlike a drop of water on a lotus leaf that stays on it without drenchingit in the least. If, notwithstanding instructions of Panchasikha of themendicant order, thy knowledge has become abstracted from the sensualobjects to which it relates? Thou hast, it is plain, fallen off from thedomestic mode of life but thou hast not yet attained to Emancipation thatis so difficult to arrive at. Thou stayest between the two, pretendingthat thou hast reached the goal of Emancipation. The contact of one thatis emancipated with another that has been so, or Purusha with Prakriti,cannot lead to an intermingling of the kind thou dreariest. Only thosethat regard the soul to be identical with the body, and that think theseveral orders and modes of life to be really different from one another,are open to the error of supposing an intermingling to be possible. Mybody is different from thine. But my soul is not different from thy soul.When I am able to realise this, I have not the slightest doubt that myunderstanding is really not staying in thine though I have entered intothee by Yoga.[1709] A pot is borne in the hand. In the pot is milk. Onthe milk is a fly. Though the hand and pot, the pot and milk, and themilk and the fly, exist together, yet are they all distinct from eachother. The pot does not partake the nature of the milk. Nor does the milkpartake the nature of the fly. The condition of each is dependent onitself, and can never be altered by the condition of that other withwhich it may temporarily exist. After this manner, colour and practices,though they may exist together with and in a person that is emancipate,do not really attach to him. How then can an intermingling of orders bepossible in consequence of this union of myself with thee? Then, again, Iam not superior to thee in colour. Nor am I a Vaisya, nor a Sudra. I am,O king, of the same order with the, borne of a pure race. There was aroyal sage of the name of Pradhana. It is evident that thou hast heard ofhim. I am born in his race, and my name is Sulabha. In the sacrificesperformed by my ancestors, the foremost of the gods, viz., Indra, used tocome, accompanied by Drona and Satasringa, and Chakradwara (and otherpresiding geniuses of the great mountains). Born in such a race, it wasfound that no husband could be obtained for me that would be fit for me.Instructed then in the religion of Emancipation, I wander over the Earthalone, observant of the practices of asceticism. I practise no hypocrisyin the matter of the life of Renunciation. I am not a thief thatappropriates what belongs to others. I am not a confuser of the practicesbelonging to the different orders. I am firm in the practices that belongto that mode of life to which I properly belong. I am firm and steady inmy vows. I never utter any word without reflecting on its propriety. Idid not come to thee, without having deliberated properly, O monarch!Having heard that thy understanding has been purified by the religion ofEmancipation, I came here from desire of some benefit. Indeed, it was forenquiring of thee about Emancipation that I had come. I do not say it forglorifying myself and humiliating my opponents. But I say it, impelled bysincerity only. What I say is, he that is emancipated never indulges inthat intellectual gladiatorship which is implied by a dialecticaldisputation for the sake of victory. He, on the other hand, is reallyemancipate who devotes himself to Brahma, that sole seat oftranquillity.[1710] As a person of the mendicant order resides for onlyone night in an empty house (and leaves it the next morning), even afterthe same manner I shall reside for this one night in thy person (which,as I have already said, is like an empty chamber, being destitute ofknowledge). Thou hast honoured me with both speech and other offers thatare due from a host to a guest. Having slept this one night in thyperson, O ruler of Mithila, which is as it were my own chamber now,tomorrow I shall depart.

“Bhishma continued, ‘Hearing these words fraught with excellent sense andwith reason, king Janaka failed to return any answer thereto.'”[1711]