Chapter 291

“Yudhishthira said, ‘O thou of mighty arms, tell me, after this what isbeneficial for us. O grandsire, I am never satiated with thy words whichseem to me like Amrita. What are those good acts, O best of men, byaccomplishing which a man succeeds in obtaining what is for his highestbenefit both here and hereafter, O giver of boons!’

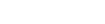

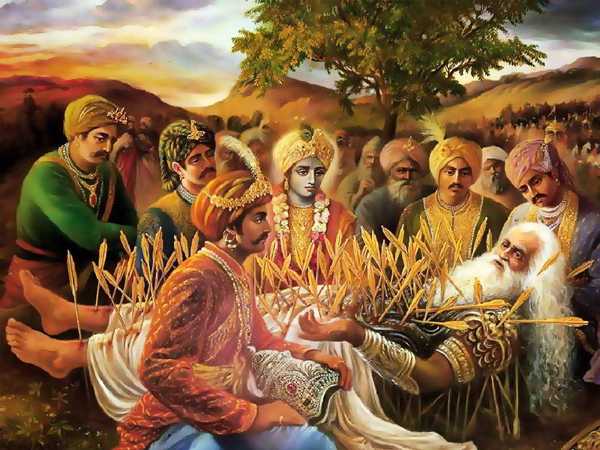

“Bhishma said, ‘In this connection I shall narrate to thee what thecelebrated king Janaka had enquired, in days of yore, of the high-souledParasara, ‘What is beneficial for all creatures both in this world andthe next! Do thou tell me what should be known by all this connection.’Thus questioned, Parasara, possessed of great ascetic merit andconversant with the ordinances of every religion,[1497] said these words,desirous of favouring the king.’

“Parasara said, ‘Righteousness earned by acts is supreme benefit both inthis world and the next. The sages of the old have said that there isnothing higher than Righteousness. By accomplishing the duties ofrighteousness a man becomes honoured in heaven. The Righteousness, again,of embodied creatures, O best of kings, consists in the ordinance (laiddown in the scriptures) on the subject of acts.[1498] All good menbelonging to the several modes of life, establishing their faith on thatrighteousness, accomplish their respective duties.[1499] Four methods ofliving, O child, have been ordained in this world. (Those four methodsare the acceptance of gifts for Brahmanas; the realisation of taxes forKshatriyas; agriculture for Vaisyas; and service of the three otherclasses for the Sudras). Wherever men live the means of support come tothem of themselves. Accomplishing by various ways acts that are virtuousor sinful (for the purpose of earning their means of support), livingcreatures, when dissolved into their constituent elements attain todiverse ends.[1500] As vessels of white brass, when steeped in liquefiedgold or silver, catch the hue of these metals, even so a living creature,who is completely dependent upon the acts of his past lives takes hiscolour from the character of those acts. Nothing can sprout forth withouta seed. No one can obtain happiness without having accomplished actscapable of leading to happiness. When one’s body is dissolved away (intoits constituent elements), one succeeds in attaining to happiness only inconsequence of the good acts of previous lives. The sceptic argues, Ochild, saying, I do not behold that anything in this world is the resultof destiny or the virtuous and sinful acts of past lives. Inferencecannot establish the existence or operation of destiny.[1501] Thedeities, the Gandharvas and the Danavas have become what they are inconsequence of their own nature (and not of their acts of past lives).People never recollect in their next lives the acts done by them inprevious ones. For explaining the acquisition of fruits in any particularlife people seldom name the four kinds of acts alleged to have beenaccomplished in past lives.[1502] The declarations having the Vedas fortheir authority have been made for regulating the conduct of men in thisworld, and for tranquillizing the minds of men. These (the sceptic says),O child, cannot represent the utterances of men possessed of true wisdom.This opinion is wrong. In reality, one obtains the fruits of whateveramong the four kinds of acts one does with the eye, the mind, the tongue,and muscles.[1503] As the fruit of his acts, O king, a person sometimesobtains happiness wholly, sometimes misery in the same way, and sometimeshappiness and misery blended together. Whether righteous or sinful, actsare never destroyed (except by enjoyment or endurance of theirfruits).[1504] Sometimes, O child, the happiness due to good acts remainsconcealed and covered in such a way that it does not display itself inthe case of the person who is sinking in life’s ocean till his sorrowsdisappear. After sorrow has beep exhausted (by endurance), one begins toenjoy (the fruits of) one’s good acts. And know, O king, that upon theexhaustion of the fruits of good acts, those of sinful acts begin tomanifest themselves. Self-restraint, forgiveness, patience, energy,contentment, truthfulness of speech, modesty, abstention from injury,freedom from the evil practices called vyasana, and cleverness,–theseare productive of happiness. No creature is eternally subject to thefruits of his good or bad acts. The man possessed of wisdom should alwaysstrive to collect and fix his mind. One never has to enjoy or endure thegood and bad acts of another. Indeed, one enjoys and endures the fruitsof only those acts that one does oneself. The person that casts off bothhappiness and misery walks along a particular path (the path, viz., ofknowledge). Those men, however, O king, who suffer themselves to beattached to all worldly objects, tread along a path that is entirelydifferent. A person should rot himself do that act which, if done byanother, would call down his censure. Indeed, by doing an act that onecensures in others, one incurs ridicule. A Kshatriya bereft of courage, aBrahmana that takes every kind of food, a Vaisya unendued with exertion(in respect of agriculture and other moneymaking pursuits), a Sudra thatis idle (and, therefore, averse to labour), a learned person without goodbehaviour, one of high birth but destitute of righteous conduct, aBrahmana fallen away from truth, a woman that is unchaste and wicked, aYogin endued with attachments, one that cooks food for one’s own self, anignorant person employed in making a discourse, a kingdom without a kingand a king that cherishes no affection for his subjects and who isdestitute of Yoga,–these all, O king, are deserving of pity!'”[1505]