Chapter 219

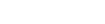

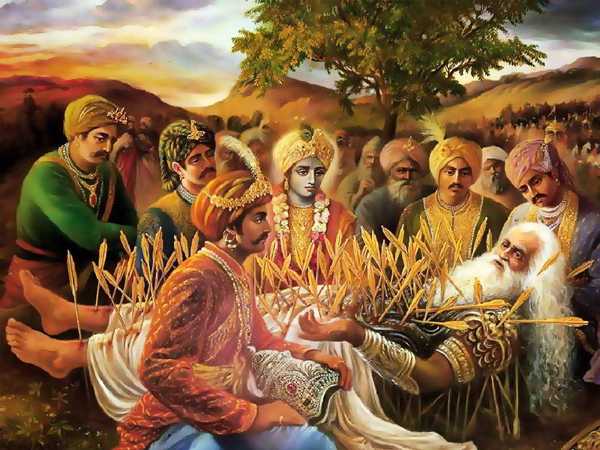

“Bhishma said, ‘Janadeva of the race of Janaka, thus instructed by thegreat Rishi Panchasikha, once more asked him about the topic of existenceor nonexistence after death.’

“Janadeva said, ‘O illustrious one, if no person retains any knowledgeafter departing from this state of being, if, indeed, this is true, wherethen is the difference between Ignorance and Knowledge? What do we gainthen by knowledge and what do we lose by ignorance? Behold, O foremost ofregenerate persons, that if Emancipation be: such, then all religiousacts and vows end only in annihilation. Of what avail would then thedistinction be between heedfulness and heedlessness? If Emancipationmeans dissociation from all objects of pleasurable enjoyment or anassociation with objects that are not lasting, for what then would mencherish a desire for action, or, having set themselves to action,continue to devise the necessary means for the accomplishment of desiredends? What then is the truth (in connection with this topic)?’

“Bhishma continued, ‘Beholding the king enveloped in thick darkness,stupefied by error, and become helpless, the learned Panchasikhatranquillised him by once more addressing him in the following words, ‘Inthis (Emancipation) the consummation is not Extinction. Nor is thatconsummation any kind of Existence (that one can readily conceive). Thisthat we see is a union of body, senses, and mind. Existing independentlyas also controlling one another, these go on acting. The materials thatconstitute the body are water, space, wind, heat, and earth. These existtogether (forming the body) according to their own nature. They disuniteagain according to their own nature. Space and wind and heat and waterand earth,–these five objects in a state of union constitute the body.The body is not one element. Intelligence, stomachic heat, and the vitalbreaths, called Prana, etc., that are all wind,–these three are said tobe organs of action. The senses, the objects of the senses (viz., sound,form, etc.), the power (dwelling in those objects) in consequence ofwhich they become capable of being perceived, the faculties (dwelling inthe senses) in consequence of which they succeed in perceiving them, themind, the vital breaths called Prana, Apana and the rest, and the variousjuices and humours that are the results of the digestive organs, flowfrom the three organs already named.[814] Hearing, touch, taste, vision,and scent,–these are the five senses. They have derived their attributesfrom the mind which, indeed, is their cause. The mind, existing as anattribute of Chit has three states, viz., pleasure, pain, and absence ofboth pleasure and pain. Sound, touch, form, taste, scent, and the objectsto which they inhere,–these till the moment of one’s death are causesfor the production of one’s knowledge. Upon the senses rest all acts(that lead to heaven), as also renunciation (leading to the attainment ofBrahma), and also the ascertainment of truth in respect of all topics ofenquiry. The learned say that ascertainment (of truth) is the highestobject of existence, and that it is the seed or root of Emancipation; andwith respect to Intelligence, they say that leads to Emancipation andBrahma.[815] That person who regards this union of perishable attributes(called the body and the objects of the senses) as the Soul, feels, inconsequence of such imperfection of knowledge, much misery that provesagain to be unending. Those persons, on the other hand, who regard allworldly objects as not-Soul, and who on that account cease to have anyaffection or attachment for them, have never to suffer any sorrow forsorrow, in their case stands in need of some foundation upon which torest. In this connection there exists the unrivalled branch of knowledgewhich treats of Renunciation. It is called Samyagradha. I shall discourseto thee upon it. Listen to it for the sake of thy Emancipation.Renunciation of acts is (laid down) for all persons who strive earnestlyfor Emancipation. They, however, who have not been taught correctly (andwho on that account think that tranquillity may be attained withoutrenunciation) have to bear a heavy burthen of sorrow. Vedic sacrificesand other rites exist for renunciation of wealth and other possessions.For renunciation of all enjoyments exist vows and fasts of diverse kinds.For renunciation of pleasure and happiness, exist penances and yoga.Renunciation, however, of everything, is the highest kind ofrenunciation. This that I shall presently tell thee is the one pathpointed out by the learned for that renunciation of everything. They thatbetake themselves to that path succeed in driving off all sorrow. They,however, that deviate from it reap distress and misery.[816] Firstspeaking of the five organs of knowledge having the mind for the sixth,and all of which dwell in the understanding, I shall tell thee of thefive organs of action having strength for their sixth. The two handsconstitute two organs ok action. The two legs are the two organs formoving from one place to another. The sexual organ exists for bothpleasure and the continuation of the species. The lower duct, leadingfrom the stomach downwards, is the organ for expulsion of all used-upmatter. The organs of utterance exist for the expression of sounds. Knowthat these five organs of action appertain or belong to the mind. Theseare the eleven organs of knowledge and of action (counting the mind). Oneshould quickly cast off the mind with the understanding.[817] In the actof hearing, three causes must exist together, viz., two ears, sound, andthe mind. The same is the case with the perception of touch; the samewith that of form; the same with that of taste and smell.[818] Thesefifteen accidents or attributes are needed for the several kinds ofperception indicated. Every man, in consequence of them, becomesconscious of three separate things in respect of those perceptions (viz.,a material organ, its particular function, and the mind upon which thatfunction acts). There are again (in respect of all perceptions of themind) three classes, viz., those that appertain to Goodness, those thatappertain to Passion, and those that appertain to Darkness. Into themrun, three kinds of consciousness, including all feelings and emotions.Raptures, satisfaction, joy, happiness, and tranquillity, arising in themind from any Perceptible cause or in the absence of any apparent cause,belong to the attribute of Goodness. Discontent, regret, grief, cupidity,and vindictiveness, causeless or occasioned by any perceptible cause, arethe indications of the attribute known as Passion. Wrong judgment,stupefaction, heedlessness, dreams, and sleepiness, however caused,belong to the attribute of Darkness. Whatever state of consciousnessexists, with respect to either the body or the mind, united with joy orsatisfaction, should be regarded as due to the quality of Goodness.Whatever state of consciousness exists united with any feeling ofdiscontent or cheerlessness should be regarded as occasioned by anaccession of the attribute of Passion into the mind. Whatever state, asregards either the body or the mind, exists with error or heedlessness,should be known as indicative of Darkness which is incomprehensible andinexplicable. The organ of hearing rests on space; it is space itself(under limitations); (Sound has that organ for its refuge). (Sound,therefore, is a modification of space). In perceiving sound, one may notimmediately acquire a knowledge of the organ of hearing and of space. Butwhen sound is perceived, the organ of hearing and space do not longremain unknown. (By destroying the ear, sound and space, may bedestroyed; and, lastly, by destroying the mind all may be destroyed). Thesame is the case with the skin, the eyes, the tongue, and the noseconstituting the fifth. They exist in touch, form, taste, and smell. Theyconstitute the faculty of perception and they are the mind.[819] Eachemployed in its own particular function, all the five organs of actionand five others of knowledge exist together, and upon the union, of theten dwells the mind as the eleventh and upon the mind the understandingas the twelfth. If it be said that these twelve do not exist together,then the consequence that would result would be death in dreamlessslumber. But as there is no death in dreamless slumber, it must beconceded that these twelve exist together as regards themselves butseparately from the Soul. The co-existence of those twelve with the Soulthat is referred to in common speech is only a common form of speech withthe vulgar for ordinary purposes of the world. The dreamer, inconsequence of the appearance of past sensual impressions, becomesconscious of his senses in their subtile forms, and endued as he alreadyis with the three attributes (of goodness, passion, and darkness), heregards his senses as existing with their respective objects and,therefore, acts and moves about with an imaginary body after the mannerof his own self while awake.[820] That dissociation of the Soul from theunderstanding and i the mind with the senses, which quickly disappears,which has no stability, and which the mind causes to arise only wheninfluenced by darkness, is felicity that partakes, as the learned say, ofthe nature of darkness and is experienced in this gross body only. (Thefelicity of Emancipation certainly differs from it).[821] Over thefelicity of Emancipation also, the felicity, viz., which is awakened bythe inspired teaching of the Vedas and in which no one sees the slightesttincture of sorrow,–the same indescribable and truth concealing darknessseems to spread itself (but in reality the felicity of Emancipation isunstained by darkness).[822] Like again to what occurs in dreamlessslumber, in Emancipation also, subjective and objective existences (fromConsciousness to objects of the senses, all included), which have theirorigin in one’s acts, are all discarded. In some, that are overwhelmed byAvidya, these exist, firmly grafted with them. Unto others who havetranscended Avidya and have won knowledge, they never come at anytime.[823] They that are conversant with speculations about the characterof Soul and not-Soul, say that this sum total (of the senses, etc.) isbody (kshetra). That existent thing which rests upon the mind is calledSoul (kshetrajna). When such is the case, and when all creatures, inconsequence of the well-known cause (which consists of ignorance, desire,and acts whose beginning cannot be conceived), exist, due also to theirprimary nature (which is a state of union between Soul and body), (ofthese two) which then is destructible, and how can that (viz., the Soul),which is said to be eternal, suffer destruction?[824] As small riversfalling into larger ones lose their forms and names, and the larger ones(thus enlarged) rolling into the ocean, lose their forms and names too,after the same manner occurs that form of extinction of life calledEmancipation.[825] This being the case, when jiva which is characterisedby attributes, is received into the Universal Soul, and when all itsattributes disappear, how can it be the object of mention bydifferentiation? One who is conversant with that understanding which isdirected towards the accomplishment of Emancipation and who heedfullyseeks to know the Soul, is never soiled by the evil fruits of his actseven as a lotus leaf though dipped in water is never soaked by it. Whenone becomes freed from the very strong bonds, many in number, occasionedby affection for children and spouses and love for sacrifices and otherrites, when one casts off both joy and sorrow and transcends allattachments, one then attains to the highest end and entering into theUniversal Soul becomes incapable of differentiation. When one hasunderstood the declarations of the Srutis that lead to correct inferences(about Brahma) and has practised those auspicious virtues which the sameand other scriptures inculcate, one may lie down at ease, setting atnought the fears of decrepitude and death. When both merits and sinsdisappear, and the fruits, in the form of joy and sorrow, arisingtherefrom, are destroyed, men, unattached to everything, take refuge atfirst on Brahma invested with personality, and then behold impersonalBrahma in their understandings.[826] Jiva in course of its downwarddescent under the influence of Avidya lives here (within its cell formedby acts) after the manner of a silk-worm residing within its cell made ofthreads woven by itself. Like the freed silk-worm again that abandons itscell, jiva also abandons its house generated by its acts. The finalresult that takes place is that its sorrows are then destroyed like aclump of earth falling with violence upon a rocky mass.[827] As the Rurucasting off its old horns or the snake casting off its slough goes onwithout attracting any notice, after the same manner a person that isunattached casts off all his sorrows. As a bird deserts a tree that isabout to fall down upon a piece of water and thus severing itself from italights on a (new) resting place, after the same manner the person freedfrom attachments casts off both joy and sorrow and dissociated even fromhis subtile and subtiler forms attains to that end which is fraught withthe highest prosperity.[828] Their own ancestor Janaka, the chief ofMithila, beholding his city burning in a conflagration, himselfproclaimed, ‘In this conflagration nothing of mine is burning.’ KingJanadeva, having listened to these words capable of yielding immortalityand uttered by Panchasikha, and arriving at the truth after carefullyreflecting upon everything that the latter had said, cast off his sorrowsand lived on in the enjoyment of great felicity. He who reads thisdiscourse, O king, that treat of emancipation and who always reflectsupon it, is never pained by any calamity, and freed from sorrow, attainsto emancipation like Janadeva, the ruler of Mithila after his meetingwith Panchasikha.'”